Before starting out on this, three simple points: First, this chapter is longer than the other chapters. It gives you insights into how I have witnessed and engaged in international “affairs”, as they call it, during my lifetime, and builds a foundation for the rest. And you do not have to read every word of it. But I had to write every word of it.

Secondly, let me remind you and myself about how short and small all human life and each human life is in the larger scheme of things. That is not to diminish its importance or our responsibilities – it’s just to maintain some sense of proportion.

You and I come and go, and it doesn’t change the world that much. We are each a tiny element in something infinitely bigger than any one of us can imagine. It should compel us to be humble, careful and appreciative – rather than grab whatever we can whenever we can.

Thirdly, writing about personal and global history imposes a sort of chronology – “see, these events and trends were what influenced and shaped me.” What follows in this chapter is not an attempt to write any place’s history but functions merely as a kaleidoscopic and yet somewhat systematic background to my activities back then and now. I have frequently inserted links, mostly to Wikipedia, to help provide background because I recognise that today’s younger people may know little about some of the events, trends and places I deal with. As an educator, I have always seen it as my duty to help people learn more – deeper – than whatever I could provide.

🔶

Hungary 1956, Dag Hammarskjöld, the Cuban Missile Crisis & JFK’s murder

▪️ The Soviet invasion of Hungary in early November 1956 was the first international event I have some little memory of. I grew up in a large villa in Aarhus, Denmark, and I used to play with my toy cars on the floor in our living room, seeing my fathers shoe sole, trousers and the back of the newspaper behind which he sat for hours – now and then sharing his thoughts in a low voice with my mom.

It was an atmosphere silently oppressive enough to be felt by a five-year-old boy – although, of course, I had no idea about the event as such or the risks and crisis feeling it entailed.

▪️The UN Secretary-General, Dag Hammarskjöld from Sweden, was killed in autumn 1961. I kind of knew what the UN was and had learned about some of its organizations, UNESCO and UNICEF in particular, at school. I knew it was an organisation for good and that Hammarskjöld was a man that many admired for his discipline and vision. Again, when he died in that plane crash in Africa – I had no idea exactly where it was – I understood from the silent and solemn atmosphere in my home that something terrible had happened.

▪️The Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 hit me hard. From my parents, their conversation with each other and with their friends who came visiting during the two weeks it lasted, I began to understand something that was entirely new to me, namely that huge bombs existed and that they had some magic power. I heard people say that this was probably the beginning of the end. Of everything.

From what I could pick up and read – at least the fonts’ size on the newspapers’ front page – my mom and dad, my brother, and other family members including my beloved grandmother could all be destroyed. I am not sure I had any sense or could imagine, that that destructive power even applied to the rest of humanity.

▪️️Only thirteen months later, in November 1963, US President John F. Kennedy was murdered. During a theatre performance that evening, my parents had been informed about it and came home in shock telling my nanny, my brother and me about it. With my dawning political interest and widening perception of a big world out there, I knew very well who he was – also from TV – and felt how terrible this was for the United States and the world.

We had a modern teak wood television cabinet with doors. Behind them was the black-and-white velvet glass screen with rather blurred images which took quite some time to appear. There was only one radio and television source, the Danish Broadcasting Corporation (Danmark Radio), that had immediately broken off its scheduled programs to report on what had happened. We sat glued into the night.

Undoubtedly, the images from that human and political drama have remained stamped on my visual – photographic – memory ever since. Enigmatically, it conveys the brutality of politics in general and the violent foundation of the US society in particular. It should be remembered that JFK was murdered only a few months after he had delivered his phenomenal and philosophical peace speech on June 10, 1963. He spoke about a new way of thinking about security and peace, about a new global order and a new relationship with the Soviet Union and declared general and complete disarmament the end goal. He knew it would be controversial, the story told here.

Did he also sense that he could be liquidated for it?

Had the United States pursued his vision in that speech – which was by no means utopian – what a wonderful world we could have had today. The best chance to do just that was the Fall of the Wall and of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact in 1989.

It was squandered too.

🔶

Martin Luther King, Jr., the Civil Rights Movement, China’s Cultural Revolution, the Student Rebellion, the Prague Spring, nonviolence and detente

▪️Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered in April 1968, Robert F. Kennedy in June 1968. That violence was an integral part of politics and of American society became even more clear to me, now a high school student (1967-1969). While I must admit that I had not studied his background, deeds or importance, I was taken aback by the fact that a man of religion and peace rather than a political leader would be liquidated in cold blood. But genuine peace was extremely controversial – already then.

When some 25 years agi I participated in a conference at the Carter Center in Atlanta, Georgia – to give a lecture and bring a message from some local Serb leaders in Yugoslavia to President Carter – I took time off to visit The King Center. While that made a lasting impression on me, it is still the social science basis, his devotion to Gandhi and his spell-binding speeches that move me today.

Over the years, I’ve often consulted my favourite King book that has this lovely Gandhi-King photo on its cover as well as the amazing Stanford University MLK Jr.’s Paper Project.

Those 1950s and 1960s were saturated with everything “America”, the saviour of Europe as the understanding was, the great ideal. JFK and Jackie Kennedy personified hope, progress and high ideals of freedom and a charismatic elegance not seen since. And there were those showy American cars (my father had a 1948 Chevrolet Fleetmaster), the Holywood films, the rock’n’roll – oh, Elvis! – and all the new household gadgets. I tasted Coca Cola for the time when in Hamburg with my parents; it had come to Germany with the US soldiers.

▪️The disastrous Cultural Revolution in China took place from 1966 to 1976. I had no idea about that faraway culture and society, and we heard little about it. However, there was always references here and there to the broader “yellow peril”. A couple of classmates and I at Aarhus Cathedral School asked our history teacher whether she could set off one lesson so we could learn a little about it. But her answer was negative. She thought that Denmark in the Middle Ages and the architecture of that old Cathedral (of which she was an expert) next to our school was much more important.

About five years later, I began to read Mao Zedong’s writing about conflicts, dialectics and the peasant-based revolution. So different from the mechanical thinking of Karl Marx. What I detested was their acceptance, if not glorification, of violence without any reflection. Gandhi was deeper – means-are-goals-in-the-making. Don’t try to create a better, more peaceful future by violent means. There is a deeper connection – and Martin Luther King, Jr. had grasped it better.

Although I did not perceive it that way at the time, it was a first tiny illustration of how self-centred the West is and how narrow-minded expertise can be.

▪️The civil rights movement in the United States – and not the least the songs by Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Pete Seeger, Joan Baez and – more than anyone – Bob Dylan influenced my political thinking. Folk and protest songs became “in” to listen to. I began to collect folk music records from around the world and record music from radio programs on the family’s portable B&O tape recorder which was a “wow” experience back then.

That movement and those songs marked my first encounter with racism, class divisions, segregation etc. – and other dark sides of the otherwise ideal(ised) American society and culture, which so intensely reached my young and curious mind. President Lyndon Johnson talked about starting a war on poverty in 1964, 15% of the American people living under the poverty line. How could that be, I thought? And today one may ask, how can it still be as high as 12,3% while China has abolished poverty?

Martin Luther King was the one who made the connection between the race issue and civil rights on the one hand and the Vietnam War, on the other. The direct and the structural violence, the different types of wars that were rooted in the fundamental militarism.

▪️Growing up in a liberal-conservative milieu, I had enrolled as a member of the Danish Conservative Party’s high school association in 1968 and later Conservative Youth and Students. In the latter’s magazine, I wrote at least one article arguing that it was too bad that General Westmoreland did not get the US troops that he required to win that war.

Fortunately, I got wiser and left that party two years later. I never joined another party. One reason I did get wiser was that the headmaster of the Aarhus Cathedral (High) School, Aage Bertelsen, was a leading Danish pacifist and consistently invited, or provoked, his pupils to think about the bigger issues – such as war and nuclear weapons – and to understand that the meaning of education and learning was to become a qualified and active citizen. He also told us about his personal meetings with the two Alberts of his life – Schweitzer and Einstein. (More about him later).

I spent 1967-1969 at that school. It was a great social, psychological wake-up and liberation – an experience that shaped my life. But it was only decades later that I found out how it did.

▪️While at high school, Paris May 1968 happened in conjunction with rebellion, or revolt, in other spheres of society – such as education, ways of living, music, art, flower power, the hippy culture – you name it. The older generation was out; we young people do things differently, to hell with all authority; Uproar is the new normal.

Bob Dylan had changed the world of music and poetry with his debut album in 1962 and songs such as “Blowin’ In The Wind” the year after and “The Times They Are A-Changin'” in 1964. The Rolling Stones were in the spotlight with “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” in 1965 – about which Mick Jagger has said that “‘Satisfaction’ was ‘my view of the world’, my frustration with everything… (disgust with) America, its advertising syndrome, the constant barrage.” The Beatles released “All You Need Is Love” in 1967; John Lennon and Yoko Ono “Imagine” in 1971.

Listen to the popular music of your day and you’ll know what is happening, won’t you, Mr Jones?

That youth rebellion was left-wing, yes – but also liberal in the good sense of the word, it meant an expansion of the fields of freedom, including the freedom to dream up a better future. It was an epoch of experimenting, rewarding change and vision. It did have a dimension of humanism, fundamentally human values, solidarity across the world, and an emphasis on the spirit rather than materialism. And it was, largely, a celebration of nonviolence – of the need for peace.

▪️In early 1968, reformist politician, Alexander Dubček, had come to power as leader of the Communist Party in then Czechoslovakia. He moved quickly to implement the Prague Spring – liberalization of the cultural, social, political and economic life if the country – so much so that Moscow sent tanks and about half a million soldiers into Prague on August 21 to stop the whole thing.

It was an early warning of what was later to come – the nonviolent struggle in Poland, led by Solidarnosc, and the Velvet Revolution in 1989 in Czechoslovakia.

People in Western Europe held their breath. How brutal would it be? How would the West – US and NATO – react? Aage Bertelsen, the above-mentioned headmaster of my high school, convened all classes and tried to explain what was happening and what could happen and soothe our fears and probably his own too.

Once again, I experienced violence rear its ugly head where negotiations would have been a much better tool for all parties. The Berlin Wall had been built in 1961 and now this, what was next to come?

However, this formative experience contained a particular element – nonviolence. I documented how the Prague people’s nonviolent action had confused the invader and how people had tried to make friends with the Russian soldiers. Violence did take its toll, but it was also a remarkable example of the power of even rather un-organised nonviolent struggle. Turn the street signs, and the tank drivers would go in the wrong direction…

It was only the year later, in 1969, the Social Democrats in Germany initiated “rapprochement” – an idea developed by Egon Bahr 1922-2015 who later played a central role as a close adviser to Willy Brandt (1913-1992) and in changing security thinking towards common security.

Brandt who had been mayor of West Berlin became Chancellor and the detente with Eastern Europe and Eastern Germany in particular – “Ostpolitik” – commenced, also inspired by Bahr. Brandt – whom I consider one of the most important politicians of post-1945 Europe was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for reducing, with concrete steps, the tension between West (Germany) and the East of Europe.

The civic dissident human rights movement, Charta 1977, came into being in 1976 and existed until 1992. In November-December 1989, the country saw the Velvet Revolution that ended all the old system’s elements and Vaclav Havel (1936-2011) took over the Presidency.

Indeed things were happening. The old system crumbled. Nuclear disarmament, nonviolence and the confidence-building measures of the OSCE – the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe – which had been established in 1975 with neutral Finland’s President Kekkonen as a central player and in which all Eastern and Western countries participated – all were indicators of the possibility of change and liberation of Europe from the role of being the pawn in the games between the Western superpower and the largest – but not super – power of the East.

In those days, there were concrete reasons to be hopeful. War avoidance and peace were self-evident elements of foreign policies. Nonviolence had taken root and peaceful mass mobilization should soon undermine the hardest of conflict structures – the Iron Curtain.

The daily risk that Europe would also become the battlefield in a third World War and most like be turned into a nuclear desert was reduced.

🔶

Student, “soldier”, activist, public figure, adviser, researcher and spy…

In 1969, high school ended, and the choice had to be made: Study first and then military service, or the other way around? At the time, I did not question the military as such, it was just something I wanted to put behind me. Since there was no immediate place for me in the conscripted army system of the time, I took some courses in the history of ideas given by a pedagogue of God’s grace, theologian, humanist existentialist and Shakespeare translator Johannes Sløk (1916-2001), at Aarhus University. I’ve returned to two of his 60 books, the one about Existentialism (1964), the other “The Theatre of the Absurd and The Preachings of Jesus” (1968, my translations). Sløk was also a co-author to a textbook about the History of Ideas In Europe (1963) – the only textbook I took with me from Aarhus Cathedral School.

This was the first time I encountered existentialism – afterwards plunging myself into Jean-Paul Sartre’s book on the subject – and acquired an openness to the idea of absurdity, or absurdism, that has helped me live as a citizen in the nuclear age and work against militarism and other violence as well as against nuclearism. And that is where I’ve always reminded myself that Albert Camus tells us that “one must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

When I had finally joined the army, I spent three months learning how to stop thinking – quite a change from professor Sløk! – and how to kill with a bayonet; then followed nine months with the medical corps. I write elsewhere about that somewhat unconventional experience – and how immensely useful that military service later turned out to be for me.

▪️My studies at the Department of Sociology at Copenhagen University – before leaving for Lund in Sweden in 1971 – will also be dealt with elsewhere. They became impossible – theoretically and practically – due to the hard science-political conflict between dogmatic positivists and no less dogmatic Marxists that was part and parcel of the Western youth rebellion.

Perhaps because I read books by both camps, I could belong to neither. These years shaped my basic attitude to scholarly work and its “schools” in the direction of keeping a healthy distance from all dogmatism and dichotomisations and either/or thinking. It tends to promote confrontation instead of dialogue. And as somewhat of an eclectic mind, – oh, Gandhi! – I’ve been drawn to combine what people generally think can not go together.

While all the above-mentioned things happened in Europe, I had both begun studying sociology (1970 in Copenhagen, 1972 in Lund) and come into contact with peace and conflict research.

Simultaneously, I began being used as a public lecturer invited by schools, people’s colleges, labour unions, peace and women’s and other movements and political youth organisations in Denmark, Sweden, and other Nordic countries. I became a sought-after public figure because, from 1974 to 1994, I wrote columns, debate articles, feature articles, and book reviews for the leading – then liberal and originally pacifist-oriented – Danish daily, Politiken. And I was used by the Danish Radio and sometimes TV in particular as a commentator and analyst of security and peace events and trends.

Members of various political parties in Denmark and Sweden consulted me, in one case I formulated part of a party program concerning security, disarmament and peace. I often met decision-makers at town hall meetings as I did military people and defence intellectuals. And those were also the days where you could hardly write a critical article without an MP or minister feeling the need to respond.

Debates and dialogue was the order of the day. There was an alert public debate. Of course, I never thought it was enough, but it was paradisal compared to the decades that followed.

I defended my doctoral dissertation in sociology at Lund University in January 1981 – “Myths Of Our Security. A Critical Study of Danish Defence Policy in a Development Perspective” (in Danish). It was the first of its kind about Denmark and also included the first systematic study of the Danish defence industry and of all the US military research and development in Greenland. Surprising to myself, it became a sort of textbook for peace activists too and sold in 7000 copies – and it was the original dissertation, not a popularised version. I remember condescending academics hinting that if it was read by so many citizens, it must be a lousy dissertation.

While working on it, I was honoured to be accused of being a spy by the Danish Chief of Defence, G. K. Kristensen (1928-2001). He called me up to his HQ in Vedbaek north of Copenhagen. Behind his large desk, he leaned forward and told me in so many words that I ought to be very very careful in the future. He maintained that putting together data and create a complete picture of such matters – even if based entirely on open sources – could be judged as espionage. He also organised that three officers in uniform turned up at the defence of my PhD at Lund University to check whether I – a Danish citizen – stood there in neutral Sweden and talked about military secrets in NATO Denmark!

After retirement, Kristensen joined Generals for Peace and Disarmament and we met now and then at public meetings and shared the memory of our – absurd – encounter in a friendly, respectful manner. Uniforms do something to people – whether green on the outside or intellectual-ideological on the inside.

During all the 1980s, I was an expert member of the Danish government’s Security and Disarmament Political Committee – and open advisory forum consisting of parliamentarians, scholars, journalists, military people and advisers from the relevant ministries. I was proud to later learn that it was then prime minister, Anker Jørgensen (1922-2016) and minister for Nordic affairs and, de facto, disarmament minister, Lise Østergaard (1924-1996) – and the first female professor of psychology at Copenhagen University – who had appointed me.

I’ve always cherished dialogue with decision-makers. I was curious to learn how they would see the world and think about concrete issues about, which I had completely different attitudes. And as a scholar, I thought it was only natural to share whatever I knew with them, not just sit on the outside and denounce what they did. I’ve done that with numerous people abroad and in conflict and war zones. And exclusively with positive results.

Regrettably, the opportunities to do so disappeared around the turn of the century and September 11, 2001.

Now a little jump back in time.

🔶

The War on Vietnam and my life in Somalia

▪️The War on Vietnam/Resistance War Against America (1955-1975) was formative too. It was there every day from I was a child until I was 24. The image of President Nixon shamefully departing the White House became iconic for me, the mighty US had lost to tiny poor peasant Vietnam with much higher morale. I wonder whether that was not the beginning of the process we are witnessing today, the decline and fall of the US Empire. Warfare consumes your own soul and violence; it never only hits the object but also the subject.

In 1998, my wife, Christina, and I went to Hanoi to learn about its tremendous post-war development and talk with various people about reconciliation – the enigmatic process through which the Vietnamese could go on and also cooperate with the United States that had done unspeakable harm to them.

Buddhism, of course, had something to do with it. The little ‘Napalm Girl’ running out of her village and how she later reconciled with the American who (most likely) was responsible for her suffering) is also one of the most beautiful stories ever told. I have used it innumerable times in my lectures to illustrate that, yes, forgiveness is an alternative to living the rest of your life with hate.

It should be remembered that one of the major US hawks and war criminals, Secretary of Defence, Robert S. McNamara, spent his last decades going back and forth to dialogue with the Vietnamese enabling him to write two amazing books that advocate a new US world policy – Wilson’s Ghost in particular. And there is his documentary In the Fog Of War. What makes people repent, forgive and reconcile in a serious way is one of the many subjects we need much more research on and media attention to.

▪️I went to Somalia in 1977 with my first wife, Astrid. We were young scholars looking for a place to do something new and pioneering outside our own culture, a place where everybody else had not gone before to do studies. She studied landscape architecture and ecology and was very engaged in the women’s movement. I was into sociology and interested in studying development. I wanted a break from conflict studies, security, armaments and militarism.

In the eyes of leading Africa experts, such as Basil Davidson, after the non-violent coup d’etat by Mohamed Siad Barre and his fellow soldiers on October 21, 1969, Somalia’s socio-economic development was perhaps the most innovative and constructive in all of Africa in the 1970s. It was still among the world’s poorest, if not the poorest, but there was something totally fascinating in it for the two of us.

It was the beauty of the country, the sand dunes, the ocean, the red mud roads and the – here and there, at least – lush vegetation. It was the immense pride of the Somalis – with their own language, poetry, songs and dances – and the beauty of those long slim men and women. Elegant movements beyond anything you could see in Europe. And it was the tremendous creativity in getting the most out of little.

We always stayed close by the ocean in Muqdishu at a small white guesthouse owned by Amina Basbas, the daughter of a former minister of British Somaliland; incidentally, it was the same street where the country’s only printing press was (Somalia was an oral culture and not before 1972 did it get a Latin script). And it was always such a joy to fly into colourful Muqdishu from Nairobi which, in comparison, we felt was sadly imprinted by almost 60 years of British colonialism (and not a place you walked the streets after dark). I never felt in danger in Somalia, and while we were there, it was normal to see parliamentarians and even ministers enjoy a meal with their families at the restaurant. They had no bodyguards, and you could walk over and greet them. In many ways an egalitarian society with the quality of safety despite being materially poor.

The day we arrived for the first time to Muqdishu’s airport – as members of a study group of the Somali-Swedish Friendship Association – everybody was standing listening to transistor radios. We felt an intense, low-voice atmosphere, anxious and solemn faces all around. It turned out that that was the day when Somali government troops had crossed the border into Ethiopia’s Ogaden Desert, one of the five territories that the Somali people had been opened for partition by the Berlin Congress in 1884 – that is, British Northern Somalia, Italian Southern Somalia, Kenya’s Northern Frontier District, Djibouti and then Ethiopia’s Ogaden Desert) that is also indicated by the five-pointed star on Somalia’s flag.

The most homogenous people on the African continent had begun the continent’s most thorough fragmentation, thanks to its clan divisions and thanks to foreign influence and power games. It remains to this day, and Allah only knows for how much longer.

We travelled the country extensively in – and on – the land rovers of the day. Given either the red gravel roads or tarmac roads with more holes than tarmac, one could indeed talk about a pain in the ass after some six or more hours per day of driving. Domestic flights were not recommendable; I remember one where we could see the landscape and the landing strip through a hole in the floor.

We made friends with countless people at all levels and got to know Prime Minister, Omar Arteh Ghalib (1930-2020) rather well. He was one of the most respected politicians of his country and still its greatest international diplomat. He put Somalia on the world map in both the UN Security Council and the Arab League. He shaped the world’s largest organisation of Muslims, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, IOC, all of which you may read more about here.

Our friendship led Omar to suggest that he would help us adopt a child, perhaps even one of his own seven children; we wanted to adopt a child but anyhow ended up not doing so. He also facilitated a long interview with president “Jaalle” Siad Barre; he was known to sleep during the day and work during the night. So it took place at his villa at 3 AM, and poor Omar who was supposed to also be the interpreter at some point dozed off to the amusement of the three of us.

It was the first time I experienced things that I have kept close to my heart and mind ever since:

a) how Somalia was materially poor but also independent, full of pride, creativity, joy, cultural activities, poetry and sensuality – and thus very rich in a different sense than in my culture;

b) how they looked upon whites – small Somali children in the countryside would often throw a little gravel or small stones on us to see whether we white people reacted as real humans – but expressed no racist attitude in general when meeting us;

c) how incredibly self-reliant, strong and resistant nomadic cultures are, able to survive under the hardest conditions;

d) how we must never underestimate how much more people know about the West than we know about them; at the time, the Somali language was oral only and had no alphabet. As I said above, no books were used in schools, education was based on oral instruction. However, adult nomads in even the remotest regions knew a lot about Sweden – Olof Palme and Pippi Longstocking and our welfare system – and the rest of the world because they listened 24/7 on their transistor radios to the BBC Somali Service at Bush House in London. In contrast, lots of people back home in Sweden and Denmark didn’t know where Somalia was on the world map;

e) that culture shock is a two-way street. For us, it was definitely a shock to arrive in a black society where there were extremely few whitings and travel around the country to places where white people were basically never seen. And then there was the culture shock when returning to the opulent West seeing fat people again, stressed people burdening themselves with shopping presents for Christmas and displaying none of the elegance, pride and joi de vivre we had come to love so much there on the Horn of Africa;

f) top leaders can be rather uninformed because no one wants to bring bad news; Barre proudly told us about the achievements throughout the country and mentioned also how a cement factory outside Berbera had just started production. He could not know that we had been there earlier the same week and there were only a few women working on the concrete foundation in the inhumanly hot sunshine.

Forever, Somalia gave me a sense of proportions and taught me how essentially important it is to try to see your own culture, society and ways of doing things from the outside, through the eyes of ‘the others.’ Its importance in my life, at that very time, can hardly be underestimated.

The frequent long-term visits to Somalia ended abruptly in 1981. Political tension increased, Siad Barre’s leadership got more and more authoritarian, the war with Ethiopia destroyed much. When we had arrived and contacted our network and asked a friend about this or that other friend, the answer frequently was – “don’t ask for him anymore.” We could not continue our research and, sadly, never returned.

We were indeed very young but pioneered the Swedish research focus on Somalia, thanks also to a small scholarship we obtained from the Swedish development research agency, SAREC.

▪️In 2014 I went to Somaliland on a trip arranged for Swedes by the young, non-recognised country’s informal ambassador in Sweden, Rhoda Elmi. Somaliland consists basically of the former British part of Somalia with Hargeisa as its capital. In this photo documentary from Somaliland, you’ll see what it looks like today.

But you will find a – to me, at least – rather moving story about another Somali I am deeply grateful to have met, its first medical doctor, a chief visionary ideologue of the party and President of the National Academy of Sciences and Arts, Mohamed Aden Sheikh “MAS” (1936-2010). We could always walk up to his office, no appointment, and he would teach us more about Somali culture, history than probably any other.

Thanks to president Siad Barre’s increasing paranoia, he put MAS – one of his own relatives – into solitary confinement for no less than six years. However, in the outskirts of Hargeisa was now a modern children’s hospital built in honour of Mohamed.

In our basement, there is still a rather large archive of original materials we collected during those four years. Perhaps one day, I will activate it. I feel there is something I should finish, something I must pay back. But to do so, I must go back to Muqdishu and surroundings. It may still take a long time before it is safe enough, and one can do fact-finding.

🔶

Europe from Cold War 1 to Cold War 2

▪️ If Vietnam and Somalia were my Non-Western formative experiences, the Europe-centered Cold War (1945-1989) was the third permanent factor that shaped me both as a European and a scholar. This conflict between the Soviet Union/Warsaw Pact, on the one hand, and the US/NATO on the other was between two versions of the same Occidental culture – socialism/communism/one-party and capitalism/liberalism/multiparty.

This implied that there were so much the two had in common in ways of thinking. Both focused on their differences and on “winning” the competition and both embarked on missions to convert others to adopt their particular version of Westernness. The Western West “won” that competition, interpreted itself as the only possible and therefore only-good system but has, in reality, been declining since 1990. It is destined to go the same way as the Soviet Union because the Western global dominance system – no matter its version – is simply not the sustainable system humanity needs. And it seems now also unable to radically reform itself.

Given this interpretation of the shared “Westernness” of the two, I had a rather sceptical view when colleagues and many others talked about the peace dividend and how – now after the Fall of the Wall – Europe and the world would become a much better place.

Instead, I had predicted as early as 1981 that the West would fall – and I had spelt out how it applied to both the Wests. But I must admit that I had no clue at the time that the Western West would play its cards that stupidly, triumphalistically and self-destructively. I wish that we had dialogued with Gorbachev about that new European House and kept our promise to him about not expanding NATO an inch and had really secured that a reunited Germany would be neutral and not a NATO member.

I’ve lived all my life with the risk of nuclear war on European soil. It was a turning point of historical proportions when Europe was liberated from a whole category of nuclear weapons by the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, INF, that Gorbachev and Reagan signed in 1987. It was a huge victory for common sense, peace and the many and diverse CSOs – civil society organisations – in the East and West who had fought for it from the bottom-up. (I call them CSOs while NGOs today have developed rather much into Near-Governmental Organisations).

No one has a right to force others to accept such a risk in their lives – except if a referendum has been held and shown a vast majority in favour of possessing nuclear weapons. The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) is a milestone both legally and normatively: these weapons must be abolished before they abolish humanity.

We should all rise against those who have nuclear weapons and make these weapons a tragic parenthesis in the human civilisation’s development. More about that later.

While I visited Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union quite a few times during the 1970s and 1980s, I never liked the system; I did it because I believe in respect, bridgebuilding and dialogue. And in solidarity with those who suffer.

The hated Berlin Wall cracked open on November 9, 1989. The weeks leading up to this meltdown of the Iron Curtain belongs to the most surprising of my life. You heard stories and witnessed events that were, simply put, unthinkable, surreal.

My wife Christina and I celebrated and drank champagne together with the East and West Berliners at New Year’s Eve 1989-90 and hammered on that disgusting, shameful Wall the next days. We still keep some lumps of it as an eternal reminder that all forms of authoritarianism shall eventually go.

The unthinkable can be thought. Good things can happen.

There is hardly any doubt that that First Cold War has solidified my deep aversion, bordering on hatred, of armed confrontation in general and nuclear weapons in particular. No one had the decency to ask me whether I would accept to live under the Damocles Sword of militarism and nuclearism? Who has a right to force me to accept that I shall leave this world knowing that my children and grandchildren are likely to live – or to die – under it too? Do not tell me that the West is a true democracy when citizens have never been allowed to give their opinion about this existential matter.

Do not try to convince me that this is the best, most ethical, safe and logical system to create and preserve security and peace. It creates neither.

Instead, take away the funds available to advocates of militarism and nuclearism – or reduce it to the level we peace people have to operate on. And then let the one win the debate who argues best, most convincingly and wins the trust of the citizens. Or, let peace be financed by tax money and let the MIMAC – Military-Industrial-Media-Academic Complex elites finance theirs by fund-raising from citizens, bake sales and unpaid labour.

▪️ In what was nothing more than a nanosecond in global history, the US/NATO West immediately after 1989 found new enemies. Behind such a drive are strong forces; I call their consolidated structure MIMAC – the Military-Industrial-Media-Academic Complex – much broader, deeper and destructive than the Military-Industrial Complex that US President Eisenhower had warned his country and the world about in his farewell speech in 1961.

MIMAC wouldn’t survive without the manufacturing of threats that build up fears in the minds of taxpayers who, at the end of the day, finance militarism. The post-1989-enemies were Somalia, Saddam in Kuwait, Serbia, Afghanistan, Saddam in Iraq, North Korea, Libya, Syria – and Iran all the time and – believe it or not – Russia for a second time!

The starting point of this Second Cold War was a failed US attempt at regime change in Ukraine and the EU’s and other West’s – foolish – idea to get Ukraine into the Western fold. Although the only future possible for Ukraine is to remain neutral, be pampered by both and be a partner of both. Here 106 articles on my foundation’s old website.

I believe that this is a basic truth: Western political culture cannot live without images of enemies. That is why it was most significant when Russian political scientist, top-adviser and institute director, Georgy Arbatov (1923-2010), stated that “We are going to do a terrible thing to you, we are going to deprive you of your enemy” – as ex-CIA analyst Graham Fuller elaborates on here.

In other words, when we could have had a new peaceful Europe today, the US/NATO and the EU chose to prioritize the expansion of NATO, thereby making the old border with Russia even harder and exploiting Russia’s weaknesses at the time. By definition, humiliation with triumphalism can bring nothing good.

NATO now consists of ten countries what used to be Warsaw Pact members and neutral countries that were useful as soft buffers – such as Sweden and Austria and Yugoslavia – either are now pro-NATO or do not exist. Russia’s military expenditures are 8% of those of NATO’s 29 members and falling – while the old Warsaw Pact’s expenditures used to be 65-75% of NATO’s. But who cares about such facts in today’s militarist climate imbued with fake and omission inside a falling hemisphere?

Neither NATO nor the EU seems to have the vision or the coherence, to adapt to the new situation – whether the demise of Yugoslavia, the 2015 refugee flows or the Corona pandemic. Both both show conspicuous signs of fragmentation and lack of leadership.

🔶

Japan over 20 years

▪️ Now a huge jump to my life in Japan. I’d been to Japan before and worked with Japanese peace scholars both in Lund and elsewhere. The nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as well as the country’s unique peace constitution – in the famous Article 9, Japan renounces war and the maintenance of a war potential – would make Japan exceptionally well-suited to promote peace as well as research on various aspects of peace.

“Would…” I said because the reality is very different. Japan’s de facto security and foreign policy is one long, incremental deviation from that unique pacifist norm as it has not been capable to liberate itself from US remote control.

Although I had visited China in 1983 as a Danish cultural delegation member and was sure that China would absorb me from then on, it did not work out like that. Thanks to various coincidences and encounters, I came to live altogether for almost two years as a visiting peace studies professor at the International Christian University, ICU, in Mitaka outside Tokyo, at Chuo University, two times at Nagoya and, finally at Ritsumeikan University in my favourite Japanese town of Kyoto, in total spanning 1990 to 2010. And I did not return to China until 2018 – but from now on it will indeed occupy me.

Among my special joys in Japan was to get acquainted with the lay Buddhist movement of Soka Gakkai International, SGI. With around 12 million members (at the time), it must be the world’s largest peace organisation too – becausepeace is what it is passionate about together with Buddhism.

I was invited to guest lecture at Soka University outside Tokyo in the mountainous and amazingly beautiful area surrounding the city of Hachioji. I spoke later at local SGI chapters here and there in Japan. The spiritual leader – Sensei – of Soka Gakkai is Dr Daisaku Ikeda (1928-). For some reason, Soka people had obviously let it go up through the hierarchy that I worked for peace because, in 1995, my wife Christina and I were invited to a conversation with Sensei Ikeda, which started out very formally in a huge hall with Soka notabilities seated along the walls.

At some point, he asked whether he could now invite my wife to a more intimate tea room – to which I said that that would be OK if I could then take his charming female interpreter to another room. That kind of broke the ice, and people laughed. I have always had a hard time with formal ceremonies in general and always think of Danish entertainer and humorist Victor Borge’s (1909-2000) famous dictum that “Laughter is the shortest distance between two people.”

After many sips of tea and delicious cakes, he said to me that he had an offer to make, but before he told me what it was, he would like me to say “Yes”. I said, “Eh… Yes” – big smiles. The offer was that he wanted me to become the director of a new SGI peace research institute that SGI planned to establish at Okinawa – inside the buildings of an abandoned rocket launcher base where rockets had pointed for years against China.

It belongs to the story that Ikeda-Sensei had opened up the very sensitive relations between China and Japan in 1974 by visiting China’s first Premier, Zhou Enlai (who died in 1976). So placing a peace institute in an environment that signified no more enmity between the two appeared to me to be brilliant.

For various reasons, however, that institute was never built, and I didn’t have to live up to the offer I had not refused. But SGI did take me on a trip to Okinawa – the place where there is a very moving memorial park called The Cornerstone of Peace for everybody who died (more than 240 000) in the “Tennozan” Naval Battle, history’s allegedly largest, in 1945. It’s interesting in that everyone who died – military and civilian, war criminals and innocent people – have their names engraved in black marble walls. Okinawa is also partly occupied by US bases that the Okinawans have wanted for decades to get rid of.

Be this as it may, Buddhism has always been close to my heart, and I maintain contact with many Soka friends. Ikeda-Sensei gave me many presents, including his collected works and his books with his amazingly beautiful photographic works. In 1996 I was awarded an honorary doctor’s degree at Soka University. Perhaps most touchingly, Daisaku Ikeda wrote a chapter about me – “The Peace Doctor” – in his book, “One By One”, about great dead and living people who have changed the world for the better. Well, we all make our mistakes, but it was anyhow a great honour 😉.

My generation will remember how from the 1950s, Japan spearheaded Asia’s economic and management miracle and inspired the four “tiger economies” – Singapore, Taiwan, Hongkong and South Korea. My uncle bought one of the first Toyota cars in Denmark, and we’ve all been consumers of exquisite miniaturised Japanese products – computers, cameras, the walkman, tape and video recorders. We’ve enjoyed the elegant aesthetics in handicraft and fashion, been amazed by Zumo wrestling and plunged ourselves into one of the world’s most beautiful and healthy cuisines. I’m a self-taught maker (not master) of sushi, which used to be workers’ street food.

However, when I arrived in Japan in spring 1990, the miracle had begun to crack. For the first time in modern, wealthy and relatively egalitarian Japan, there were people living in the streets, parks and under bridges. And those who did not, either pretended not to see them or explained that they were just people experimenting with living far away from their incredible luxury and boredom. It was also a country that had embraced Westernization in lifestyle, food, entertainment etc. while – and that must be emphasized – always preserving its Japaneseness at the bottom.

I tend to think that we in the West actually never really understood the Japanese. We saw them as highly efficient and almost inhumanly hard-working high-tech producers and mass consumers – only. However, I learned that Japan is much more enigmatic, sophisticated and therefore interesting as culture and society and in terms of ways of thinking – “social cosmology”. For instance, the fact that a Japanese citizen plays many different roles every day and that all attitudes and behaviours are contextual – i.e. depends on the situation and the structure in which it takes place – cannot but make a sociologist highly curious.

Another aspect is the capacity for accommodating contrasts. Most citizens of Japan take very active part in the consumerist lifestyle – I’ve never seen Christmas shopping like that in a country where less than one per cent are Christians. More surprising to the foreigner is how much they also love walks in the woods and mountains, meditate, go to temples to turn their faces to various gods and their backs to fellow-citizens. And the ability also to mix new and old – be it architecture, ways of doing things, city planning, keeping up old traditions and handicraft while frequenting “electronic cities” to find the latest gadgets they – probably – don’t really need but group pressure and fashion tells them to buy.

Everybody who has seen the central railway station in Kyoto knows what I mean.

In that sense, it is strangely inward-looking, orderly, stable and working smoothly when everything is normal. But the moment something unexpected – big or small – happens, the whole system stalls. That’s also why it has stagnated over these thirty years where I have followed it.

And it has lost to China on virtually all important indicators. In 1990, almost everything you picked up in a store was “Made in Japan.” From around 2000 it was as more frequently “Made in China.”

I’m grateful beyond words for all I’ve learned about living differently in safe, decent, polite and smiling Japan. Those who taught me most about Japan were my students – both Japanese and foreign who had lived there over a longer time. I’d told them that they could always knock on my office door; no Japanese professor had ever done that, so I got lots of young boys and girls coming around trusting me as a confidant. They had an almost desperate need to talk with someone neutral.

Japan has at least two levels. An upper, visible which is quite Westernized such as the multiparty system, a military alliance and submissive foreign relation with the US, consumerism and an amazing interest in everything Western, including classical music. Below and way into the countryside, through the rice fields and up the mountains along the Buddhist temple trails, you still find the real, never-changing Japan. These years gave me the opportunity to learn how to operate in a culture very different from the West.

It’s a thoroughly good society to live in also because you can hardly ever become an integrated member of it. The Japanese remain unique, stagnating or not. And the foreigner remains forever a foreigner – a gaijin.

I can truly say that I ❤️ Japan.

🔶

Yugoslavia – my third country

▪️And now back to Europe and another love story – Yugoslavia. It begins in 1974 in Dubrovnik at the Adriatic coast in what is now Croatia. That’s where there was a multi-national Inter-University Centre, IUC. Professors from all republics came there to teach philosophy, literature, politics, international affairs, etc – and their students came from around the world. Not so strange because about 120 universities around the world delivered the non-Yugoslav students and teachers free of charge to the IUC. So it was an international meeting place like no other between East and West – and Yugoslavia was a neutral, non-aligned country with amazing relations with both the East and West and the so-called Third World.

One of the teachers at IUC was Håkan Wiberg (1942-2010) who was also one of my sociology professors at Lund University. He had stimulated my interest in peace and conflict research because he gave a short introductory course to it. He was also the head of the Lund University Peace Research Institute – or Department – LUPRI (closed down in 1989). He must have sensed my interest because one day he said, Come along with me to Dubrovnik, I think it will be an eye-opener for you!

And so I did. And so it was.

At the time, the director of IUC was Johan Galtung, whom I had met when he gave a lecture at my high school in Aarhus in 1968. So, here I was with two pioneering eminent and very different peace scholars who became my main mentors in the field of peace and conflict research. The first years I was a student, took all the courses I could and wrote one paper after the other; we called it high-temperature education. Apart from some sleep, a sista with lunch – often oysters and white wine at some beautiful square in the old town – and a swim in the sea, it was work, work and more work until late dinner and then up early the next morning. In particular, Galtung was a super-productive creativity-driven master who inspired young people East, West, North and South… in the end, however, too much for the Yugoslav authorities.

As you’ll see here and there through this book, they are guilty of much when it comes to my intellectual career and production.

Later, I became a teacher at ICU and enjoyed it tremendously – also because it gave me the opportunity to learn from some of Yugoslavia’s best intellectuals – including the Praxis philosophers, people like Mihailo Markovic and Svetozar Stojanovic.

Interestingly, Josip Broz Tito – the “dictator” as ignorant people in the West called him after his death in 1980 – had an interesting way of treating thinking dissidents; he took their passport from them and, so, the only place they could interact with scholars from abroad was in – yes, Dubrovnik. That was great for me because I learned one thing in 1974 that I could not have operated without later: Yugoslavia was hellishly complex; don’t believe that you understand it because you have read a book or two. Always look for various explanations, be aware that everything is related to everything else in the Yugoslav space and – finally – don’t believe that the Balkans is a kind of backyard of primitive thinking and atavistic conflicts.

Concretely – there I sat as a 23-year-old student and listened into the wee hours of the night to the – heated – discussions among the best intellectuals from all Yugoslavia’s republics discussing the most important thing that year and indeed signalling the fate of the country – the new Constitution that had been adopted in February 1974, a 300+ page document that allegedly made it the second-longest constitution in the world after that of India.

▪️ From 1974, Yugoslavia became the third country that I felt I belonged to. I have visited it more than a hundred times, almost every corner of it. With the TFF team members, I was very intensely and closely involved in all the processes of its violent dissolution through the 1990s and I have conducted about 3000 interviews in all republics, at all levels and with people of all walks of life – in addition to internationals, UN people, humanitarian workers, journalist and, on one occasion, CIA.

I have served as goodwill (unpaid) mediator between three governments in Belgrade and the Kosovo-Albanian leadership under then-President Dr Ibrahim Rugova. TFF’s team produced a comprehensive plan for a 3-year negotiated solution which was the only one that got widely published in leading media on both sides.

It was all destroyed by those who wanted a violent solution, the US, CIA, the German intelligence service and the murky Kosovo-Albanian forces that got all the weapons. They undermined Dr Rugova’s nonviolent policies and later became the Kosovo-Albanian Liberation Army, or KLA/UCK, NATO’s allies on the ground. Two of their leader still play prominent roles in the new states’ political system, Hashim Thaci and Ramush Haradinaj.

And that was basically what the 72-days NATO bombing of Kosovo and Serbia from March 24, 1999, was all about. The Clinton administration’s illegal (according to international law because it lacked a UN Security Council mandate) Serbophobic project produced nothing but destruction, fear, higher cancer rates due to the criminal use of depleted uranium bombs, 800 000 refugees who ran down to Macedonia, etc.

I was there during the bombing, visited Novi Sad and Belgrade. Remember standing in my room on the 6th floor of Hotel Moskva in the centre of Belgrade and feel the pressure wave up through my body when NATO relentlessly punded the Batanica air base, built to withstand tactical nukes, 10 kilometres away. No one who was not there would ever understand what crime it was. And the result? The US Bondsteel Base, the largest at the time outside the US, being built in Kosovo for strategic reasons, an even today failed stated called Kosova and a Serbia that has long ago lost faith in joining the West. Why?

I’ll tell you why. Law professor, Vojeslav Kostunica, who became President after Slobodan Milosevic told me during a conversation I had with him in his home in the cosy Skadarlija Street that Washington had already told him – a couple of months after NATO’s bombing – that Serbia would only be allowed to join the EU after it had joined NATO.

This deep engagement – with TFF’s several Associates and Wiberg and Galtung in particular – has produced what I believe to be the largest single analytical work, equivalent to about 2500 A4 pages, namely the blog called “Yugoslavia – What Should Have Been Done” (2014) in which everything we wrote from the wars broke out there in 1991 is published as it was originally written. It’s also unique in its systematic focus on not only criticism – of which we do a lot – but on how the world could have helped the peoples of Yugoslavia to divorce in a better way and live better together afterwards. Had the West not bee so ignorant and arrogant and mainly produced peace-prevention policies.

I remain of the belief that that conflict and the ways it was mishandled has changed Europe and certain matters beyond Europe more than the fall of the Berlin Wall and the demise of the Soviet Union.

In summary, much more to be said in due course.

🔶

September 11, 2001 – history’ most foolish war

▪️ I was on my way home from an international conference in Bucharest, Romania, about religion and peace, attended by church people of all denominations in Europe. I had a longer stopover in Munich and sat in a sauna there when someone came in and said that he had just seen some planes fly into the towers and added that it looked like a movie. I told myself that that was probably what it was. That somebody had flown planes into those towers from the top of which I had once seen all of Manhattan myself was simply too far out of my imagination. Surreal.

I soon got wiser. On my way to the departure hall, all screens showed those now-iconic images again and again as if to convince us that this was real. At the gate, it was announced that they knew nothing about whether there would be a departure to Copenhagen or not. It was a nervous, solemn atmosphere in which we felt something enigmatic and ominous had happened. But what exactly? At boarding, the staff searched us meticulously and took my Swiss knife.

Since that day, everyone knows what “9/11” means. But we’ve never learned “10/7” for the US retaliatory invasion of Afghanistan or “3/20” for the attack on and occupation of Iraq in 2003. To be able to manufacture the symbols and images that help immortalize what “we-shall-never-forget” is an important element of political power – as is the ability to shape – by silence and omission – that “about-which-we-shall-never-talk.”

Since then, everything has gone wrong thanks not to the event itself but to how the U.S. under President George W. Bush decided to react to it. At this point, let me just state these views – probably still provocative to touchy souls:

• Terrible as the almost 3 000 innocent deaths that day was and remains (of which more than 300 were not US citizens), it is a minor event in the history of violence. The U.S. response, the Global War On Terror, has been totally out of proportion and caused millions of dead and wounded and destroyed one country after the other. 37 million people have been displaced. In parenthesis, about 30 000 people are killed and wounded in domestic gun violence, and about 300 000 Americans die from obesity annually. The thousands of billions of dollars wasted on the Global War on Terror could have been used to solve the much more devastating and tragic socio-economic and class problems of the American society.

• Very conveniently for the US as a victim, everybody asked Who did it? and How did they do it? – but very few dared ask: Why did they do it? Why did they choose the United States and why its three main centres – Wall Street as its global economic power, Pentagon as its global military power and (attempted) the White House as its political power? Just a bit of diagnosis, or causal analysis, would have helped shape a better policy.

• I have never engaged in analysing what actually happened, but I remain unable to believe the official explanations – too much unasked, unexplained or dubious. What has been more important to me is to see a) how the United States has exploited the event, b) how victim psychology has been given a perverse blast, and c) how counter-productive for itself and the rest of the world this has been.

For example, according to now disappeared State Department data for the year 2000, international terrorism killed about 400 people and wounded nearly 700, mainly in South America. However, the 2020 Global Terror Index from the Institute for Economics and Peace, IEP, put the figure for 2019 at 13.826 casualties. That is 35 times more deaths from political terror actions than in the year 2000. It must be one of history’s most counterproductive ways of solving a problem and one of the most unintelligent wars ever fought. Which doesn’t mean that any high-level politician has asked the obvious question: What have we done wrong for so many years when the problem has just grown bigger and bigger?

• The whole response was wrong because the Global War on Terror remains based on the – foolish and anti-intellectual – conception that you can eradicate an ism – terrorism – by killing terrorists. You can’t. Who in their right mind would argue that we should eradicate diseases by killing those who suffer from them?

• Finally, the definition of what terrorism is has been a slippery slope from Day One. Virtually any violent act – also without any documented political purpose – can now be called terrorism if it suits governments’ propensity to use violence to respond to an event and only ask questions afterwards.

Secondly, the entire focus for 20 years has been on small-group or private terrorist activity and not on state terrorism. A generally accepted definition of terrorism – distinguishing it from war – is that it is a surprising/unpredictable and horrifying act of violence meant to achieve a political goal by deliberately harming or killing innocents people or people not a party to a conflict. With that, it is obvious that governments – not the least the US itself – are much bigger terrorists than, say, ISIS. And it should be obvious that all countries with nuclear weapons adhere to a terrorist philosophy since nuclear weapons cannot be used anywhere without the deliberate harming and killing of innocent civilians, perhaps even in the millions. That’s why, before 9/11, we used to talk about the nuclear balance of terror. But that term has, understandably, been deleted from the nuclear discourse.

▪️ What has this Global War on Terror – not September 11 as such – influenced my life?

Well, I think of George W. Bush whenever I go through ‘security’ in an airport. It has meant surveillance everywhere and a tragic reduction of general trust in our society. It has created a huge security-intelligence-surveillance complex closely related to the Military-Industrial-Media-Academic Complex, MIMAC. It has reduced the joy and excitement of travels to a minimum.

And worse, perhaps than all of this, it has undermined democracy and freedom. In the name of fighting terrorism, authorities can do exactly whatever they like (“our first duty is to protect our citizens”). You cannot argue against any of it as long as the majority believes in it for real – instead of as a pretext for permanent worldwide warfare. It has caused a series of new wars and enormous refugee problems.

Sadly, the living conditions this has forced upon humanity are not going to disappear in my lifetime. Even if terrorism should disappear completely, this new Complex will promptly find ways to legitimate its existence and further expansion. For 20 years now, politics have been conducted by deliberate “fearology” – and when you make citizens fear, they are willing to accept anything.

In conclusion, the convenient self-image of an innocent, peaceful US being attacked out of the blue is absurd. September 11, 2001, was a consequence of the foreign policy of the United States since 1945 – a blowback or boomerang. We now have an everyday psycho-political fearological state terrorism, uniformly adhered to by governments around the world and reducing tremendously the quality of life, human rights and democracy for all the world’s citizenry.

Identifying the causes – the why – of “9/11” is not the same as defending its perpetrators. That said, the reaction the US leaders in Washington chose has, in my view, long ago documented itself as a much larger moral, legal and political crime against humanity than what happened on that historic, apocalyptic day in New York and Washington.

The US chose permanent violence as its response. It could do so because it is history’s strongest military power with a global reach. Ask yourself how a country with a tiny, or no, military would have reacted to a similar event. I imagine it would have searched its soul, used diplomacy, improved its intelligence and early warning and brought up its suffering in the United Nations. And it would have used its best brains precisely because it could not choose worldwide violence, death and destruction.

🔶

Burundi – the heart-shaped country still looking for peace

▪️My quite unexpected life in Burundi started out at a conference in the US where I gave a lecture about forgiveness, reconciliation and peace-making. Afterwards, a black man came up to me, shook my hand, thanked me and said – I want you to come to my country, Burundi. He was Prosper Mpawenayo and Minister of Education. He wanted me to be a keynote speaker at a UNESCO-supported conference shortly after in the capital of Bujumbura. I immediately said “yes” – having so long wanted to get back to the African continent I had so abruptly left in 1981.

As director of TFF and head of its mission in Burundi, I was engaged on and off in Burundi – the small, very densely populated, banana and coffee-producing country in Africa with 8 million inhabitants – between 1999 and 2010. Allegedly, it was the third poorest on earth, and little had happened for decades in terms of socio-economic development.

But Burundi was a good, pro-peace story out of Africa, in the wake of war and genocide.

Nevertheless, the world over, neighbouring Rwanda has received most of the attention, and its genocide is commemorated every year. The documentaries, history books, Hollywood movies and novels are all about Rwanda. Most people do not know that they were once one country, and if you go there today and compare Kigali and Bujumbura, you would also not believe they were.

Remembering genocides is an important means of ensuring that these tragic events do not happen again. So those who know Burundi ask themselves: Why never a word about Burundi?

In the genocide there in the 1990s, at least 300,000 were killed; isn’t that worthy of commemoration in the media?

▪️ TFF did conflict-analysis and mitigation, peace education courses, skills training and in 2005-2007, we organised a new NGO, the Amahoro Coalition with 13 leading CEOs – Civil Society Organisations. Amahoro means peace. The overall idea was to train young people in conflict-resolution, negotiations, mediation etc., to help them become change agents throughout their society. Our work enjoyed the full personal support of the President of the Republic, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Speaker of Parliament and of the UN Head of Mission.

From 2007, I did two other things in Burundi. First, I had shot two video interviews in 2008 with then foreign minister, Antoinette Batumubwira. In the one here she emphasizes, among many other important things, that the good story about Burundi – and it was at the time – was complicated to spread to the world.

There was a strongly felt need to develop an international media strategy so Burundi would appear more in the media, both with its problems and as a good story out of Africa. So I worked with a ministerial team that she had appointed. When I had learned how they were thinking about such a strategy and what they needed, we made a brainstorm and, based on that, I wrote up a plan. Mme Batumubwira was quite pleased with it. However, shortly after and way before it could have been implemented, she was appointed head of the External Relations and Communication Unit of the African Development Bank (AfDB) Group and left Burundi.

Secondly, I taught the first peace and conflict course at the local, private Lumiére University. From time to time, it was pretty chaotic. The lecture hall with some 150 students was basically an open structure with a corrugated iron roof. In Africa, rain showers can be quite explosive and the noise on such a roof deafening. Since much-needed electricity for the microphone came through only a couple of hours per day – there was no way you could teach when it rained.

Be this as it may, the course went very well, but the university could not find the funds to establish a planned Masters degree in the field of peace. I must admit that I felt quite despondent about both of these developments beyond my control. Indeed, all involved did their best, but if you are at the bottom of the global society, funds are often Problem # 1. Burundi never received even half the international development aid pledged by donor countries.

▪️ To make a long story short, money also became a problem in a way I had not foreseen.

Two leading members of the youth organisation – one of whom I had taught bookkeeping – managed to empty the bank account of the organisation, funds that originated from the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and from friends of my wife and I as well as from TFF’s Friends. Although the stolen sum was small in Western eyes, it made up a few annual average incomes; it was never retrieved. A person at the Ministry of the Interior who should, upon my urgings, have intervened legally had obviously been bribed and did nothing.

None of what we had built survived after TFF’s and I had left. And I learned that there is something called inverse racism; about half of the young people seem to have thought it was wrong to do that to TFF and me personally – after all, they had had a good experience, we had had a good time together and many appreciated TFF’s work over the years. The other half was of the opinion that since I was a “muzungu” – a white man – it was not that wrong whereas it would have been a punishable crime had the money been stolen from a fellow Burundian.

C’est la vie – as they say. In 2017, I summarized what happened later:

“Burundi has been consumed by internal violence. President Pierre Nkurunziza’s main policy goal seems to be to keep himself in the President’s palace until 2034. He has stated that he has God’s mandate to do so.

On the way to achieve that goal, the Arusha Peace Accords have clearly been violated and so has the country’s constitution.

Hundreds of thousands have fled to neighbouring countries due to rampant government-instigated terror against its own people. Civil society and media have been reduced to a bare minimum. Socio-economic problems have created a huge crisis, and the country is now likely the poorest in the world in terms of per capita income. The ruling party is strong because there is no viable, cohesive political opposition.

Burundi has quit the International Criminal Court and demanded that the earlier UN missions were drawn down. The last UN Mission left the country at the end of 2015.”

I had had a long conversation with President Pierre Nkurunziza shortly after he had won the elections. I got a good impression of him at the time; as a Hutu who had taken part in the violence and lost family members, he was committed to trying to reconcile the Hutu/Tutsi divide, he said. And he promised to pray for our peace work. As the years passed, he seems to have been hit by a kind of megalomania and started his and his party’s war on the people with whom he had been extremely popular in the beginning. I’ve heard that many of my young friends fled to Uganda, Rwanda and Congo.

When the Corona struck the world, he seems to have declared that God had blessed the air in Burundi so the virus would not be a problem. However, his wife got it as well as a bodyguard, and then Nkurunziza himself fell ill and died in June 2020.

▪️ Despite the above and the sorry end of all our efforts, I am happy and in many ways grateful that I have worked in Burundi. I feel convinced that we sowed some seeds with a few minds. It gave me the privilege to work – again – in a materially poor country and appreciate my own life in the perspective of the hard lives millions – the wretched of the earth – live every day. It gave me proportions.

When on mission in Burundi, I often stayed at a villa owned by a Swedish lawyer and businessman, Magnus Schiller. He had decided to not only live in Bujumbura parts of the year but also to care for about a dozen young orphan street boys. They lived on his compound, he paid for their existence and education and also gave them genuine guidance and saw to it that they got a job and kept on the right side of the law.

I befriended him and them, began to take photos of them – and brought back the printed images at the next visit. On Sundays, we sometimes organised a minibus that took us all to the Tanganyika Lake’s wonderful beaches where we took more photos, sang, played football, drank Coca-Cola and ate sandwiches. Feeling how those happy hours there made them happy made me even happier.

Here three of them – “beach boys” – always with a glimpse in the eye and, yes, some of them turned it into a fashion show too…

I learned about a very different culture where people struggle very very hard to survive and in which economic corruption, abuse of women and of political power, unbelievably low standards of education and much else combine to condemn millions of good-hearted Burundians to poverty and a lax attitude to what I call truth. Simply to survive. Not checking what is right and what is true but believing in anything you hear – including constructed rumours – is one of the ingredients of the politics of genocide.

And – oh yes – like in Yugoslavia, I got a solid education in how wrong and self-serving the simplifying Western concept of ethnicity is.

Deep down, Yugoslavia’s dissolution was certainly not about “atavism” – something happening because of an ancient habit from a long time ago in the history of Serbs, Croats and other nations there.

And neither is Burundi and Rwanda about Hutus and Tutsis; these identities can be mobilised as part of complex conflicts rooted in poverty, inequality and the above-mentioned power abuse and, of course, in traumas. But ethnicity is not the root cause.

Perhaps, in reality, the assumptions about some kind of primitivity at lower civilisational levels that Western science, politics and media excel in is, when everything is told at the end of the day, rather more about the intellectually lazy and self-serving interpretations of cultures and conflicts that the West itself has a huge responsibility for having created in the first place?

Playing one group against another is primitive. Why? Because there has never been a complex conflict anywhere with only two parties and none in which all the good people are on one side, and all the evil people are on the other. But this is still the prevalent worldview among Western geopolitical interventionist decision-makers who operate on little knowledge about “the locals” and on a strong belief in their own superiority – that is, on contempt for those they consider morally, militarily or otherwise weaker than themselves.

There has been more than enough of Western racist colonialism in Africa – in both Somalia and Burundi. Their best hope now is to become part of the Chinese-initiated Belt And Road Initiative, BRI – or the new Silk Roads. I wish Amahoro for all Burundians. Finally.

🔶

Iraq 2002 and 2003

▪️The board of TFF had discussed what could happen in Iraq during the build-up to the bombing, invasion and occupation that began on March 19-20, 2003. Should we somehow get engaged? Not that we thought we could prevent a war, but we have always seen it as part of a serious analysis to have been to the place. Actually, that is one of the things TFF is known for in contrast to many scholars who often refrain from going to hotspots or warzones. I’ve always respected war reporters who took risks to be able to bring the rest of us news from such places.

TFF’s board chairman at the time was Stockholm-based Lieutenant Colonel (Retired) Christian Hårleman who had spent most of his professional life in numerous United Nations peace-keeping operations (PKOs) around the world and also trained lots of people. We both knew how to operate under extraordinary circumstances and getting in and out of offices in a diplomatically correct manner. We did two missions to Iraq – one via Amman, Jordan, and one to Damascus, Syria, after which 800 kilometres by car to Baghdad. The latter was in February 2003 and upon arrival, we made an agreement with the Norwegian embassy that if the bombing should begin while we were there, we would be protected at the embassy. But we left well before hell descended upon the Iraqi people.

We conducted some 160 interviews at all levels. The Iraqis were extremely open to talk with us as visitors because all their attempts to dialogue with the US and the EU/NATO world had come to nothing. Letters they wrote to the EU requesting exchanges were never even answered. During our visits, we were mostly in Baghdad, of course, but also in Babylon and Basra and we visited the UN mission on the border with Kuwait, UNIKOM.

Upon our return to Sweden, we wrote numerous articles, gave interviews and commented on various media. TFF had more than 15 Associates with deep knowledge about the Middle East. At that time, it was possible to get through in the media with a variety of perspectives; editors thought it was interesting to convey what those few who had actually gone to a conflict or war zone had seen and heard – the independent, free voices. We also thought that that was the very least we could do in gratitude to the hundreds of hours our interlocutors had spent with us.

Between March 27 and May 2003, I wrote a diary of the events with critical observations of most of the media coverage – entitled “Think Freely About Iraq” encompassing 54 articles/comments. I also wrote a book in Danish the title of which in English would be “Predictable Fiasco. The Conflict With Iraq and Denmark As An Occupying Power”. It was published already in early 2004 while lots of research is often published way after events have taken place. I had thought it would make a splash in Denmark because Denmark’s participation in the occupation of Iraq under Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen was the largest (till then) foreign policy miscalculation in Denmark since 1945 and the one with most lies embedded in its foundation.

However, it sold only 10% of the copies of my more general dissertation “Myths About Our Security” had done in 1981. That made me wonder whether thick analytical books were rapidly becoming less productive at least when it comes to the global affairs field than online publishing. Whatever the answer, I haven’t published a printed book since then.

▪️Who did we meet, interview and learn from?

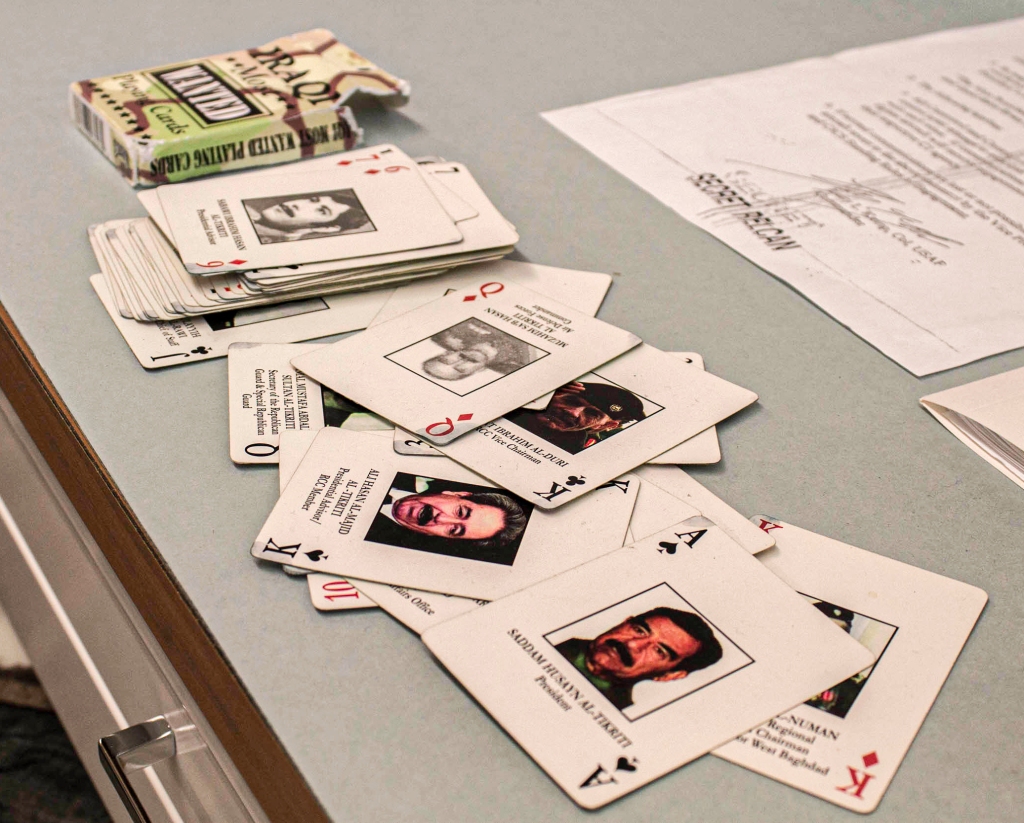

American military authorities had issued a deck of cards consisting of the “Most Wanted Iraqis” – people who have since then, by and large, been liquidated, imprisoned or died in custody. By 2021, only 11 of them have been released.