And how the mainstream media became the largest single obstacle to an understanding of our complex world.

“Let us not forget that violence does not live alone and is not capable of living alone: it is necessarily interwoven with falsehood. Between them lies the most intimate, the deepest of natural bonds. Violence finds its only refuge in falsehood, falsehood its only support in violence … And no sooner will falsehood be dispersed than the nakedness of violence will be revealed in all its ugliness – and violence, decrepit, will fall.”

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Speech at the Nobel Banquet at the City Hall in Stockholm, December 10, 1974

Gandhi would agree with Solzhenitsyn but express it in a slightly different way. Gandhi argued that all violence implies a reduction of truth. Truth has countless elements – like a big tree with countless branches and leaves. Cut a branch, and you have reduced Truth. If we use violence, perhaps kill another human being, we reduce truth. You can never know whether you had all the information about that person – it may later turn out that you had been deceived or made the wrong judgement of her or him. The moment you have used violence, the world becomes less true – and the violence will harm you too.

One may add that those who use violence become strongly motivated to cover it up and explain it away. Lie to themselves and the world and, thus, promote falsehood.

Our media are tremendously important for our understanding of reality – the world out there that we are all part of. A huge majority, perhaps 98% of the world’s people, cannot or do not travel to places – and certainly not to conflict and war zones – to see for themselves, explore and draw their own conclusions as to what it is about. Reporters do – they do the job for most of us and, together with their media leaders, including editors and owners, they decide what we shall know, what we don’t need to know and how we shall think about various issues in international politics – or world affairs.

In other words, people understand the world – and develop a worldview as well as their personal opinions – through the media. It is true that some read books and monitor world developments on the Internet, but however valuable, such knowledge is also transferred through specific contextualised lenses.

That said, I believe, therefore, that it is important to report my experiences with the media, not the least because I can see trends over time and because I belong to the few who, like reporters, travel and see things with my own eyes and hear with my own ears. Thus, I can compare the media reality with my professional analyses and perception of real reality. I can see what it is the public – or media consumers, as they are called nowadays – get and don’t get.

•

I’ve been participating in various types of media work since the mid-1970s. I’ve always believed that if you are an academic at a university, you have a duty to speak to general, non-academic audiences. After all, it is the citizens who have paid for your education.

Nothing gives you better training than public lecturing and media work. As Einstein has allegedly once stated, you have not understood a problem before you can explain it to a person in the street. I believe that to be true, and it’s regrettable that academics are still not trained to do so as part of their education.

Typically, in a media setting, you get a couple of minutes to explain something which you know is perhaps rather complex. In order to be successful, you’ll have to brutally kill many of your darlings and get the essential elements of facts and their relations across, even prepare to use words with signal value, use metaphors or whatever one finds pedagogically helpful. And above all, you must: a) know your subject (or say no to participate), b) prepare yourself well, make notes on a piece of paper, repeat in front of a mirror at least until you have gained some experience, and c) never read from your notes or a manuscript when you’re on.

You must also accept that in direct media or ‘live’ programs, you’ll likely feel a little nervous every time. And that that is when you perform the best.

I’ve done it a few thousand times in many types of media and in different countries. Over these years, I have experienced how media work has changed, how the expert’s role has changed, how the ways you are treated have changed and how the role of the media, mainstream but also some more counterstream so to speak, has changed in our society.

For the sake of good order, let me emphasize that what I say in this chapter covers only the broad Western mainstream media field of international politics. I am not competent to judge how the media operate in fields of economics, domestic politics, culture, entertainment, sports, etc.

Also, you’re welcome to run through my policy for working with mass media on my online home. I speak with anyone from any country who treats me professionally, respectfully and fairly. Over the years, I have noticed that quite a few media people believe that it’s such a privilege for people like me to be part of their program and that you are, therefore, willing to accept more or less unreasonable conditions just to reach their audiences and – as a young man once expressed it in Danish TV studio when he had decided to ignore my title and affiliation in the screen presentation – just be grateful for the ‘branding.’

This is an attitude I have encountered frequently in Western mainstream media but not among alternative ones or media in Russia, Vietnam, India, Iran and China. They seem to operate professionally and be consistently grateful for the time and energy I devote to them.

Finally, here at the outset, let me express my main conclusion – both provocative and honest: Today’s mainstream media are the single largest barrier to understanding the world we live in and where it and humanity are heading.

🔶

Glimpses of my work with Nordic and international media

My 20+ years of work for the liberal daily Politiken in Copenhagen

In my younger days, I always felt that I was treated with respect – or, rather, that, in general, there was respect for people who knew something and could convey it to readers, listeners and viewers in a pedagogical way helpful to public service. Editors wanted a diversity of perspectives on foreign and security issues, including those of conflict resolution, non-violence and peace-making.

Many of the media people I worked with were not only knowledgeable about facts and complexities, some of them also wrote books and made excellent fact-based introductions to the discussion we were going to have. There also existed an interest in what I would call the longer argument.

When you sent a manuscript to a newspaper – back then typed up on a typewriter with a carbon copy and then sent off to the editorial office or delivered by hand at the paper’s reception – you would wait a few days, and then the editor, if interested, would call you up. Or, after a little longer wait, also for postal services, a typewritten, signed letter would come back from the editor or his/her secretary that, unfortunately, this was not something they could bring at this time, but you were encouraged to send something in the future.

I remember with joy and gratitude the feature (“kronik”) editor at the time Harald Mogensen (1912-2002 and brother of the renowned furniture designer Børge Mogensen), at the Danish liberal daily, Politiken – today a pale edition of what it once was. I wrote book reviews, feature and debate articles for Politiken from the early 1970s up to 1994. He became legendary because of his habit of inviting interesting people and asking them to write about often controversial or future-oriented matters instead of just sitting and waiting for manuscripts to come in – of which he once told me that he got more than ten a day that were all publishable, but his space limits forced him to send them back. (Yes, if a manuscript was declined, it was returned to you by mail).

This very kind, warm-hearted, white-bearded and very sharp-eyed man often called me and said something like – “Jan, I have just read your manuscript. It’s fine, and I want to publish it; my problem, however, is that it is a bit too long but also so compact that I do not know where to shorten it. Could you come up to me tomorrow at 3pm to talk about it and where to shorten it so we can both be happy?”

I’m afraid I did not fully understand at the time what a privilege it was to be treated that way by one of the finest media personalities in Denmark at the time. He taught me a lot about texts, communication, clarity and how to present an argument. And normally, we quickly found a way to shorten the text, and we then had a pleasant conversation about other topical issues of the time.

Thank you for giving me your time and sharing your insights so generously, dear Harald!

I wrote feature and debate articles, reviewed books and gave comments regularly up to 1994. In that year, Politiken decided to arrange a demonstration at the central town hall square in Copenhagen, Politiken being located at one of its corners. The stated purpose was to express solidarity with Croatia and Slovenia and denounce Rest-Yugoslavia’s policies under the leadership of President Slobodan Milosevic. I felt that this was hardly a task for a trustworthy media to take a political stand in such a case and promote it by arranging a public demonstration. Thus, I wrote a feature (“kronik”) manuscript in which explained the complexities of this, perhaps the world’s most complex conflict, and stated why I thought Politiken’s editorial leadership, by arranging such a side-taking demonstration, obviously did not know the complexities but had been carried away by its own biased reporting. By then, I had been in and out of Yugoslavia since 1974 and worked intensely with TFF’s conflict mitigation teams in Yugoslavia since autumn 1991. We just happened to know it a bit better than most.

My manuscript did not merit a reply, so I called the feature editor. He told me, frankly, that my manuscript lay at the desk of the newspaper’s editor-in-chief, Tøger Seidenfaden (1957-2011). In other words, the feature editor did not enjoy autonomy, but the editor-in-chief could control that section. Very close to the Politiken demonstration, I finally got the message: It would not be republished before but only after that demonstration.

I immediately withdrew the manuscript and got it over to the – then more militarism-critical – daily, Information. As far as I understood, Seidenfaden got very upset and tried to stop it, but it was too late.

That was my second last ending with Politiken, the liberal newspaper.

In 2008, I was asked by an editor to begin writing a large-format article regularly – about one full page. I willingly accepted and wrote (in Danish) this one, “Nuclear weapons are incompatible with democracy.” The editor was very appreciative and said he looked forward to the next a month later; I approached him when that month had passed and asked what kind of subjects he would suggest. It turned out that Politiken had decided that one such article from me was enough.

And then I decided that enough was indeed enough with Politiken.

•

The Danish Broadcasting Corporation

During the Yugoslav dissolution wars, I frequently participated in the Danish Broadcasting Corporation’s foreign policy magazine, “Udefra,” – often together with the legendary expert on Eastern Europe and the Balkans, Dag Halvorsen (1934-2007). I had been a goodwill mediator between the Kosovo-Albanian leadership under Dr Ibrahim Rugova and three governments in Belgrade and also had a long conversation with president Slobodan Milosevic. Therefore, I knew that bombing Yugoslavia to carve out Kosovo as an independent state, the second Albanian in Europe, and doing so without a UN Security Council mandate would be catastrophic and prevent what my colleagues and I had worked on – namely, a plan for a three-year negotiated, peaceful solution.

After Yugoslavia, the invitations from “Udefra” to comment on international affairs stopped coming. This related, I assume, to an incident at the Danish Broadcasting Corporation.

The prime-time news program, “TV-Avisen,” asked me to comment on the prospect of NATO bombing Kosovo and Serbia. It was a few days before it actually happened. I said three things: 1) that NATO would bomb – which was something most people thought impossible because it would be a gross violation of international law and lack a UN Security Council mandate; b) that it would solve no problems there but prevent a negotiated solution; and 3) that to me, NATO looked like a smiling crocodile because it was its first out-of-area mission which also violated its own treaty.

That was in March 1999, and I have not been invited to the prime-time news programme since then.

It did not matter that what I said was true; media people I was on good terms with back then told me that it was point 3) – and that I was right – that caused this public service’s prime-time news media to never invite me again. Denmark supported the NATO war on Yugoslavia politically, and Danish F-16 took part in the bombing; it was Denmark’s debut as a bomber nation.

However, I have sometimes participated in the Danish Broadcasting’s “Deadline” and “Debatten” programmes – but I jumped off the latter because it degenerated into a chaotic shouting match with no public education relevance and little respect vis-a-vis me.

•

With “Deadline,” I had a funny experience some years ago. I was called up by a young journalist who did research and had been instructed to find out what I thought about the following question: Shall we or shall we not talk with terrorists?

I believe we should talk with terrorists simply because they are human beings with an agenda and because one major reason people become terrorists is that they feel that nobody listens to what they feel and how they see the world. After 30-40 minutes, the journalist said something like “thank you, this has been so enlightening, and I’ve learned a whole new way of looking at this. I am sure my editor wants you to participate; are you available Thursday or Friday evening this week?”

I confirmed that I could travel over the bridge from Sweden to Copenhagen and participate live if they wanted me to. He also said that I would be debating someone who was of the opinion that one should never talk to terrorists. OK with me, I said.

Then nothing happened for days, but on that Thursday, my wife and I were about to open our iPad to see the Deadline programme – when the young journalist called and apologised for not having come back to me – and told me that the format of the program had been changed. And indeed, it had; it turned out that the only person being interviewed – former foreign minister Mogens Lykketoft – repeated himself for at least 10 minutes that one should under no circumstances talk with terrorists.

I believe that it would probably have made better public service TV with two different experts, a minister and an academic – in the studio. But either someone had told the editor to not let me into that studio, or Mr Lykketoft had refused to participate if he was to debate with me. I know for a fact that at least one other foreign minister had that attitude when a few times asked to accept a public debate with me about foreign and security politics in general and Yugoslavia’s dissolution war in particular. His name was Uffe Elleman Jensen.

•

The International Herald Tribune

Prior to the US-led war on Iraq, former assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations, Hans von Sponeck, and I sent an article to the International Herald Tribune. He had resigned from more than 30 years of UN service after having served as the UN coordinator of the Food for Oil programme in Iraq and knew the country extremely well. His argument for resigning had ben as strong as it was simple: “I do not want to preside over a genocide on the innocent Iraqi people.” My background for writing was that I had been on two fact-finding missions to Iraq, and had interviewed about 160 people from all walks of Iraqi life for my 2004 book in Danish, “Predictable Fiasco.”

You may read our article, “A Road to Peace With Iraq – Europe’s Choice”, and learn how and why the IHT editor, Robert Donahue, broke his promise to publish our manuscript. The IHT of course posted lots of feature articles at the time in favour of the US intervention.

That is how editors can shape the public debate and set the agenda: Bombing was necessary or right. In all fairness, I believe that New York Times is the only important Western mainstream media that has apologised for its coverage of Iraq. But Mr Donahue never did.

•

The Swedish Television, SVT, in Stockholm

While from the early 1970s to around 2000, I was a frequent commentator and columnist in Danish media, I’ve never acquired the same position in Sweden’s media but did write articles for the cultural page of Helsingborgs Dagblad over several years. Whatever I did do in Swedish media – particularly in the Swedish Broadcast System, SVT – anyhow ended abruptly in 2006.

It was a panel debate about Iran as a nuclear threat to the world, and since a participant argued that nuclear weapons were OK for democracies but not for authoritarian states like Iran, I happened to question the extent to which one could actually call the United States a democracy:

I also pointed to the US nuclear use doctrine and argued that there was no reason for any state to possess nukes; if some have them, there will always be governments somewhere who want to have them too. Therefore, I argued that nuclear abolition would be the only effective policy. In addition, that – since in the name of civilisation, we have abolished cannibalism, slavery, absolute monarchy, etc., why not abolish nuclear weapons too? After all, the biggest terrorists are not ISIS or other peripheral groups, it’s the countries that maintain the weapons of ‘the balance of terror.’

So that was the end of my career there. I do not know, of course, but it’s reasonable to assume that someone from the US Embassy has called the editor higher up and conveyed a friendly suggestion to the effect that SVT better not invite me again.’

Again, it does not matter that what you say is fact-based and well-argued. The problem is that there cannot be critical voices and experts who can devise better policies towards disarmament and peace. Or challenge the media framework and narratives. And – of course – you cannot offer a fundamental criticism of the US and NATO in countries that are either formal members of NATO or so dearly want to become a member.

•

Svenska Dagbladet – the leading Swedish conservative daily

Another example from the days of the Yugoslav dissolution wars. I was asked by the Swedish conservative daily Svenska Dagbladet to give a longer in-depth interview about their conflict background. I accepted immediately because it was one of the Swedish media that had a reasonably balanced coverage and at least one knowledgeable editor, Fredrik Braconier.

The journalist did a fine job using a tape recorder and promised to send the text to me so I could make changes and then accept it. There was simply nothing to change, and I thanked him for his fine work. Then came the surprise: when published, the inserted subtitle stated – “…says Jan Oberg who in the debate is known to be pro-Serb.”

You’ll understand what that meant at the time. I called the journalist and asked who had added that (which I would not have accepted). ‘Well’, he said, ‘my editor said that unless that sentence was added, he would not accept the interview for publication. I am very sorry.’

I fully understood and accepted that he had wanted it to be published for its content, of course – and for the work he and I had put into it. But what the superior had felt a need to do was to frame me – to present me to the reader as someone who is on the wrong side and whose words are, therefore, less trustworthy. Remember, in those days ‘the Serbs’ were the culprits, the evils – like the Russians today. No media would have emphasised if someone was pro-Croat, pro-Albanian or pro-Muslims in Bosnia. That would have been exclusively positive – but to be pro-Serb was nothing but a pejorative characterisation serving to show politically correct. Like “Putin Versteher” today.

It goes without saying that Svenska Dagbladet never contacted me again.

•

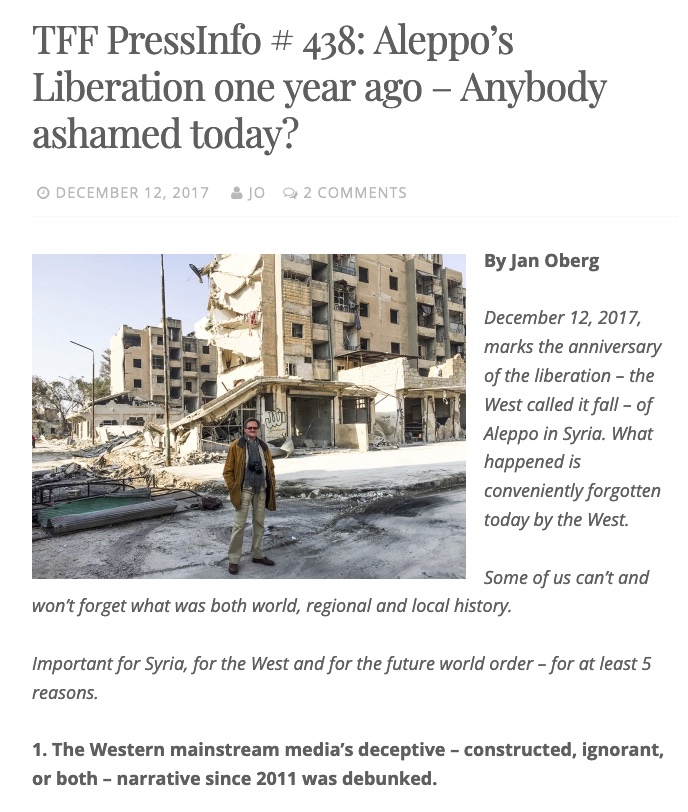

Syria – all Western mainstream media closed for alternative reporting, analyses and photos

Syria 2016 represented the biggest media fraud I had experienced up till then, while those of Yugoslavia and Iraq were not exactly small.

The way I was treated by Western mainstream media – all of them – made me conclude that the media wall was now hard and compact. No crevices, no cracks. And therefore none of the classical journalistic principles:

• diversity with the aim of securing broad public education;

• checking more sources than one, independent of each other

• independent investigative digging or seeking possible, latent truths underneath official manifest narratives.

My articles on The Transnational led Google Search to de-rank TFF, and we could see a marked decrease in clicks during spring 2017. The other result of that mission to Syria was that not one Western mainstream media published any of my texts, did an interview or reproduced my photos.

Should they? There were less than ten Western media people in Western and Eastern (occupied) Aleppo during the days I was there, namely December 10-14, 2016. On December 12, Eastern Aleppo was finally liberated from 4,5 years of occupation by terrorist organisations such as Al-Nusrah. For the first time, the citizens could walk the streets, drink a coffee and hear no immediate shooting. Children who had not been able to play in the yards and streets could now do so.

I was the only one from Scandinavia and would assume that in the normal sense of the word ‘scoop,’ my presence there and using what I heard and saw would have been just that. Here is Wikipedia: “In journalism, a scoop or exclusive is an item of news reported by one journalist or news organization before others, and of exceptional originality, importance, surprise, excitement, or secrecy.”

None of the media I alerted in the belief that they would be interested had their own people in Syria at the time.

You must understand that the liberation of Eastern Aleppo marked the end of the Western attempt at regime change that had started 5 years before. It was after this event that Syria largely disappeared from the media. The West had lost, and, some would say, the Syrian government, assisted by Russia and Iran, had won.

To see the destruction along the road from Damascus up to Aleppo and the utter destruction of Eastern Aleppo was the most shocking I’ve ever experienced. But the lack of media interest was as shocking to me, although in a different manner.

I’ve described and documented the whole experience – media by media – with excerpts of email correspondence, names and other details. I urge you to read:

Syria and Aleppo – Old news media falling – about Danish Radio 24/Seven, Information, Berlingske Tidende, DR Deadline, Swedish Sydsvenska Dagbladet, Dagens Nyheter, and others.

Unique Aleppo photos seen by over 100.000 people but not in mainstream media – namely:

My six documentary photo series from Syria

Aleppo’s Liberation one year ago – Anybody ashamed today?

The answer to the question raised in that TFF PressInfo is “No!” Nobody was ashamed or regretted their general coverage of Syria. And no one contacted me afterwards to explain their non-professional behaviour or seek mutual understanding, let alone apologize.

Most of what you heard about Syria was a well-financed, meticulously constructed narrative based on a series of fake assumptions, frameworks and selected (hi)stories – including the fraud about the White Helmets, which were also not what you were told that they were. I analysed these White Helmets before going here.

And there were all kinds of omissions, of course – the perspectives, events, expert opinions, Western crimes, alternative news bureaus – that were never let in to balance the deceptive overall Western narrative.

In sum, what I call FOSI: Fake + Omission + Source Ignorance.

•

“We cannot publish something that is so different from CNN, BBC and The Guardian”

Our media cannot deviate from the benchmark media, particularly in the US and Britain. I remember when, back in the 1990s, people in Denmark knew me as an expert on Yugoslavia who had shuttled back and forth since I was partly educated in Dubrovnik (now Croatia) from 1974 and onwards.

That was the time when younger journalists who had been assigned to go to Yugoslavia quite often called me up and asked where in Yugoslavia it would be good for them to go so that they could get their own original and “different” story which would be news- and print-worthy in the eyes of their editors. In one case, a young male journalist had been tasked by his editor to do research, go there and dispatch 5 articles back from the war. Idealistic – as virtually all of them were – he wanted to do something original or different, find new angles and even make a “scoop.”

I gave every one of them some ideas, even the names and phones of some knowledgeable people who were in my network. They left – but it took a long time before I heard from them again.

And what could they tell?

All of them either never got their articles printed or had them changed and shortened. There was one consistent reason behind that, namely that the editors had told them: Look, your reportages are certainly different and well written, but we cannot publish something that is so far from what we see every day on CNN, BBC, The Guardian (and others mentioned).

Research, originality and diversity have narrowed down tremendously since those days.

•

The proxy war in Ukraine

If Syria was a shocking experience to me, the media operation around the war in Ukraine from February 24, 2022, has been even worse and painful to witness. (Since my readers will probably wonder, I distanced myself from Russia’s invasion on February 25).

The NATO-Russia conflict that plays out through the proxy war on Ukraine’s territory has gripped and frightened European citizens in a way no other war in the – far away and culturally different, Middle East. And its victims are Christian victims and victims of Russia’s warfare; they are not Muslim victims of US/NATO lead wars.

The Western/NATO/EU response to the Russian invasion manifestly moved beyond the proportionality principle, beyond rationality and a realistic image of the world and the future.

On March 22, 2022 – as soon as the Western response to Russia’s 24th of February invasion had begun to appear – I wrote ”NATO/Russia conflict in Ukraine: The West’s spinal cord reaction will prove extremely self-destructive” on The Transnational:

“Self-righteous spinal hatred, the inner Russophobic swine dog as well as lawlessness in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will harm the Western world itself and hasten its decline and fall.

The term “inner swine dog” means, according to the English dictionary, “Malicious, hateful drive, which hides behind a person’s apparently friendly and tolerant exterior”.

This dog, which can belong to both elites and the masses, has been let completely loose among both high and low across the political spectrum. There no longer seems to be any limit to what can be said about Russians and Russia – even without a comparative perspective – and what can be done to isolate the country and its people economically, culturally, socially, financially and in the media. All with reference to Russia’s – in my view, international law-violating and unethical – invasion of Ukraine.

As if by magic – and unsurprising in a kakistocracy – the word ‘Putin’ explains everything.

The contempt and hatred must have been latent deep down in the collective unconscious for a very long time. It is probably largely a consequence of the so-called free media’s systematic, one-sided “threat assessments” over decades – again without comparative analysis with NATO’s behaviour and military overspending – and the omission of any perspective on what is Russia’s history, security needs and perception of us.

Explaining something doesn’t mean defending it. The conversation is dumbing down. The case, the substance – the ball – disappears, and all that remains is the person, ad hominem attack, categorization and positioning: “Putin Versteher,” “pro-Russian,” “anti-NATO,” “Putinist,” or “paid by the Kremlin.”

Or – ‘since you do not have the same opinion as I have, I do not need to listen to your knowledge.’

The media have taken the lead in setting the tone for the boundless hatred that has spread from the lowest instincts to concrete actions and reactive measures at the highest level of political decision-making.

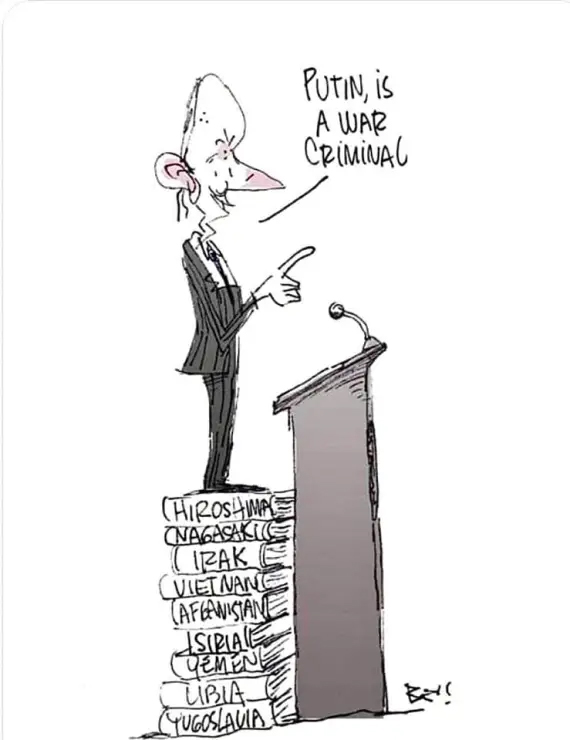

Western mainstream media have simply announced, as a fact that required no documentation, that Russia – as a country, a government and a people – is the enemy, a mortal threat against not only neighbouring states but NATO as a whole. They’ve concealed the military-economic imbalance, downplayed or left completely untold the reprehensibility of the US and other NATO countries’ wars, occupations, mass deaths, refugee creation, regime change – and failed attempts at it, as in Syria. They have distorted history and omitted essentially important facts and events pertaining to NATO policies since 1990.

The same goes for the suffocating sanctions against Iran’s innocent population of 85 million. And Israel’s bombings and nuclear weapons have long since ceased to be reported.

I, who follow these issues daily through a wide spectrum of media, have been dismayed every single day for at least the past 20 years by the obvious ways in which this is all being orchestrated – and increasingly homogenised in the clear favour of the US and NATO countries. And in favour of more war – as we see in the case of Ukraine.

Only Western sources and news agencies have been used, experts from state research institutes financed by NATO governments have been brought in by, and hardly any material has been published to shed light on Russia’s interests, ways of thinking or perceptions of what we in the NATO circle were doing. Access to leading Russian media has been cancelled; Western people are prevented from knowing the other side of the coin. It is not only a gross violation of the human right to freely seek information and shape one’s opinion, it is also expressive of a serious contempt for fairness. RT – Russia Today – does a much better job every day in telling its audiences in a quite matter-of-factly manner what happens in the West.

Free research and the freedom to report it and get heard, at least now and then, are things of the past. So is fair treatment of facts and opinions as well as of the parties to a conflict.

A media glare has run for decades. Today, ordinary people react so violently and have little idea how much they have been seduced by constant, factually ignorant good/bad – black/white – world images. By FOSI = Fake + Omission + Source Ignorance.

•

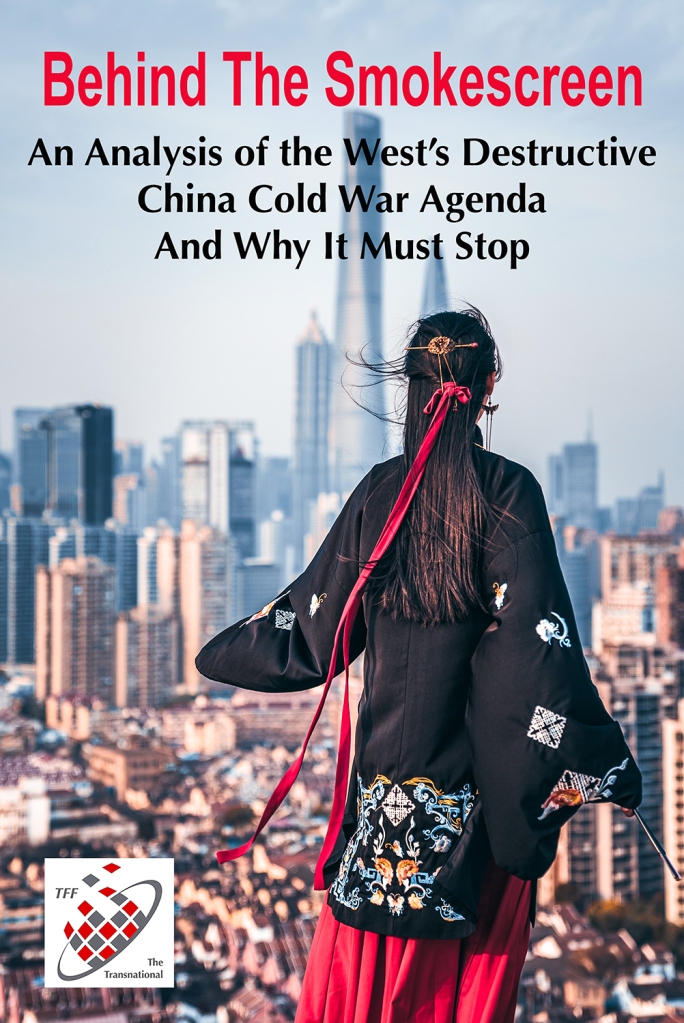

The constant China bashing

I make this section short. I visited China in 1983 and travelled around the country alone for six weeks in 2018. I’ve seen the socio-economic and cultural changes. I feel they are deeply impressive and certainly unique in contemporary human history. Simply because of that – not because China is aggressive, threatens the West or want to become the world’s new imperial leader (they are not stupid) – it’s perceived as a challenge to the West.

I am no expert on China, don’t speak the language and have never done fact-finding, research or lectured there – but I hope to, eventually. Real experts spend a lifetime understanding China and its unique civilisation and the ways of thinking of the Chinese – so different from ours in the West. However, I am going to spend a good part of the rest of my life trying to understand China, also by living and working there -also with my photographics work – during longer periods.

The reason China is constantly bashed – the reason you can find extremely little positive stories but cascades of negative aspects of it in the Western press – is that the West is in relative decline while China is ascending. It has to do with us/US much more than with them.

With my colleagues, Thore Vestby and Gordon Dumoulin – both members of TFF’s board – I have produced a report on how this is orchestrated predominantly by the United States. Here it is. Just click on the image or here, where you may also download it freely as a PDF:

The report has an intro and 11 chapters. Chapter 4 is about Smokescreening: Media Manipulation Methods (MMM) Promoted by Governments and Media. Chapter 5 is about The China Themes – and Non-Themes – in Western Governments and Media, and Chapter 6 is about Concrete Smokescreening and Media Manipulation Methods (MMM) Used Against China.

I urge you strongly to check it out yourself so you understand better how you are being taken for a ride by the mainstream media. You’ll surely be surprised to learn that US state media – such as Radio Free Asia – disseminate some of this disinformation and how the US Congress throws millions of dollars after media that promote exclusively negative stories about China.

•

No response to press releases and diplomatic letters

Finally, let me share my experience with the Transnational Foundation for Peace and Future Research, TFF, of which I am the co-founder and director. Over the decades, we have dispatched close to 700 press releases – the about-weekly TFF PressInfos – containing research-based analyses, educative and opinion articles by our highly qualified and experienced TFF Associates and others – which are published on The Transnational. They reach about 5000 people, the largest group of which are journalists and editors in the Nordic and international, predominantly Western, media.

With 2 of 3 exceptions per year, these media people never reacted to anything. We have a fairly high opening rate – about 30-35%, which is good – but reading these messages does not prompt grabbing a phone and ask for interviews, comments or articles.

Thus, they know about us. They also know that qualified alternative, peace-oriented materials are no longer relevant, perhaps no longer permitted.

Furthermore, over the last couple of years, I have written personally to some 40-50 journalists and editors concerning a variety of international issues where it is documentable that their reporting is strongly biased, fake and/or lacking even the basics for their audiences to understand those issues in a reasonably balanced way. I stuck to a very diplomatic, non-criticizing style – merely sending a report or article that presents other information, facts and interpretations, expressing the hope that it will be useful in their future work.

These letters have gone to individuals at, among others, CNN, Reuters, Danish and Swedish media, BBC, Norwegian Klassekampen, Sydsvenska Dagbladet and many others. Not one has considered worthy of a reply by even one. In one case, my question to a media panel participant was whether she would like to receive the TFF report about Xinjiang in the light of her accusations that China was responsible for the genocide on Muslims in Xinjiang. The answer was, ‘No thanks, I don’t need that!’

The admittedly old-fashioned decency to respond with a ‘thank you’ to personal letters is gone. The last cracks in the media wall filled.

•

Why do I tell you this, and where can you find me today?

I could go on and on. These examples – just the top of an iceberg – suffice to convey the gist of the manipulations. Now, why do I tell you this?

Frankly, not because it bothers me; I can do nothing about somebody blacklisting me, except keep on saying and doing what i find correct and truthful. It’s also a confirmation that your work is important. I am feel neither sentimental nor hurt. C’est la vie, as they say – and it is not about me, but about the Zeitgeist we have to endure now.

I merely want to illustrate how the system operates:

When you see a television program with some studio discussion, you see those who are there; you do not know who should have been there but were ‘cancelled’ for political reasons. You cannot see the articles that were sent to the editor of your newspaper but were turned down because they were not politically correct according to the editorial policy. (Such as the examples above).

The truth is that thanks to two developments, I have never reached as many global readers and viewers as I do today, first and foremost in China. (Some readers may question that, but my answers can be found in the media policy I developed many years ago).

One development, of course, is the emergence of the Internet and social media, which I learned to use early – like doing websites to publish texts and images on the Internet (TFF’s first is from 1997 and now an archive).

The other is a rapidly growing interest in my peace competence and perspectives by non-Western media as well as by alternative Western media – probably something that will accelerate in conjunction with the rapidly changing world order.

Since December 2021, I have served as a regular contributor to China Daily – 52 million daily clicks – and China Investment. I also contribute to other Chinese media such as Global Times, CGTN and CCTV, the national television, and the Xinhua News Agency – many of them both in English and Chinese editions. Find them all here.

Likewise, since April 2022, I serve as a regular columnist at the independent online daily, The Citizen, in India. Global Research in Canada often re-posts me, and since March 2020, The EurasiaReview (U.S.) publishes many of my articles, and so does the unique global multi-media agency Pressenza. Finally, I’ve served as a columnist with the Danish Arbejderen for years.

In contrast, no larger mainstream Swedish, Danish or other Western media show any interest in my analyses although most of them receive TFF PressInfo with everything I post as editor of The Transnational and on Jan Oberg, my online home.

I continue to believe in writing as one of the more effective nonviolent tools.

🔶

Summary of my personal experiences and some larger trends

It’s time to summarise these observations and experiences. What has happened to the mainstream media over these almost 50 years? My answers below are not the results of scientific investigation; they are my subjective interpretations of these experiences:

• Quantity up, diversity down – there were much fewer media back then, but most of them practised the duty of diversity much better than even public service today; with local radio and TV stations mushrooming, it’s up to every media to promote this or that perspective – and drop the professional ambition of being as objective as possible and using diverse sources.

A further factor is that, despite the growth of thousands of new media, there has been an ever-increasing concentration of the dominant corporate mainstream media at the national and global level.

• Quality decline and echo chamber culture – perhaps it is a natural consequence of the proliferation in publishing options and the booming of 24/7 media, but the quality has declined markedly. Media are simply much less well-edited, done with much less ‘personality’, love and professional pride. The way I was treated as a young writer – as described above by my interaction with the feature article editor at the Danish daily, Politiken – is simply unthinkable today. As a contributor, you are not cared for, and you no longer feel part of any media ‘family.’

Three other aspects of this decline in quality deserve mention: One, studio hosts don’t refrain from also becoming celebrities. Two, whereas earlier a journalist would interview an expert, s/he now often turns to another journalist. And, three, editorial offices tend to end up in groupthink – repelling whatever does not fit the chosen narrative, becoming even more convinced that ‘we cannot be wrong because so many others say the same’…

• Media pay for their own, not for expertise knowledge – today you are hardly ever paid for shorter articles or a television or radio comment. (As a matter of fact, I never had to take a loan for my education; I wrote for the media, commented on radio programs and gave public lectures).

Freelance experts need to think of what assignments provide an income; those who have a monthly salary from a state institute or company don’t have to do that. When the media no longer pay, they are more likely to turn to experts with a permanent income who won’t ask for a salary. The other side of that coin is that the media then obtain virtually only ‘Establishment’ perspectives and opinions rather than the freer, often more creative and genuinely independent perspectives.

So, the media, which pay their own staff, no longer pay for knowledge. It’s supposed to be such a privilege to be on TV.

• Less facts, more fake news and omission – the age-old rule of thumb that a piece of information must be confirmed by three sources independent of each other before it can be considered true and therefore publishable has succumbed to the fierce race of delivering the news first. I maintain and repeat as often as possible that omission is more distortive than fake. With some knowledge of your own, you may be able to smell a rat when you come across a fake story; but thinking of omission – what news items were left out, what other perspectives and interpretations were not presented and what kinds of expertise was not used – all that is much more difficult.

• Narratives have taken over – there is one, often meticulously constructed, version of the truth; alternative analyses and truths simply don’t make it to the screen or front page. These narratives are constructed to make the superior West shine as the innocent player that is constantly challenged and threatened and therefore has to assume the modern version of the White Man’s burden – which means to maintain and spread Western universal values and stop those who do not adhere to them – the contemporary mission civilisatrice – of course accompanied by more or less fake arguments about promoting democracy and freedom, human rights, liberating suppressed women, bringing better leaders through regime change.

Obviously, the mainstream media are not prone to apply investigative journalism to the narratives on which they thrive.

• Commercialisation – Commodification – news has become a commodity in the clicking and advertising media market economy; there is much more entertainment and mixed ‘infotainment’, and more sports prioritised more than before. Foreign policy pages have, in contrast, grown neither in quantity nor quality. In Scandinavia, for instance, a weekend edition may have 70 pages with only one page devoted to international affairs – which more often than not stops at the outer boundaries of the EU and, thus, covers 8% of humanity; and the culture pages have been collapsed with entertainment.

• Knowledge declined – media people with no education or experience in the field can cover international politics, security, war and peace. In the sections on sports, economy or, say, food – a certain minimum knowledge is required, if for no other reason because the readers, viewers and listeners themselves know something and can judge the quality of what they are being served.

Tragically, it is as if any inexperienced journalist can be tasked with covering the most complex global affairs. And since sports, economy, and local/national politics are still much more important to the majority of media consumers, little seems to be invested in qualified global affairs reporting.

Furthermore, the media now use ‘stringers’ rather than correspondents who stay abroad for years, know the country and region as well as their own and often would speak the local language. Every day I come across journalists whose texts are poorly written, stereotyped and not without spelling and grammar mistakes.

The decline in knowledge is indeed strange. With the development of the Internet, journalists can access knowledge much more easily than at any time earlier in human history. They can acquaint themselves with numerous sources and different interpretations of events, and they can check out knowledge-based, analytical online sites and research institutions. Despite all this, accessible from your desk, what we are presented with is more uniform and uninformed as I can remember it ever was.

• Homogenisation and uniformity – it used to be a major media professional drive to search for hidden stories, do investigative reporting and be the first to publish a new breaking story. Today, journalism has been reduced very much to editing the headlines and shortening content from stories that originate with a few major Western news agencies and channels such as Reuters, Agence France Press (AFP), Associated Press, BBC, The Guardian and CNN and have already been watered down by the national news agencies before being published.

One must wonder how this homogenisation comes about. I would suggest that it happens through these mechanisms: a) foreign influence or pressures being exercised on top editors say over a lunch; b) securing through interviews of candidates for an editorial or reporting job that she or he has the right attitude to politics as well as to working in the ‘culture’ and value system that any editorial office bases itself on; c) some kind of sanction system if an employee becomes a political trouble maker and d) taking in relatively young people who can more easily be socialised because the dearly want to make a career.

• FOSI & MIMAC – FOSI stands for Fake News + Omission + Source Ignorance. MIMAC stands for the Military-Industrial-Media-Academic Complex. Fake news is well-known and nothing new; invented stories have always been around servicing particular political purposes. What has grown exponentially, in my view, is omission: the stories, facts, background and analyses you never get; the experts who are never invited, and the news bureaus never used.

MIMAC is an extension of the Military-Industrial Complex (MIC), which President Eisenhower warned the US and the world about in his farewell address in 1961. My concept of MIMAC is broader and deeper; these complexes exercise an influence on today’s society and policy-making way more significant and parasitic way than when he warned us. My main point is that today’s (mainstream) media and relevant academia are well integrated into these complexes – synergy and symbiosis.

This explains why Western mainstream media are always on the side of Western armament, warfare and militarism – much more so than critical of them. And they assist in the agitpropaganda about threats and challenges, demonisations and accusations in the ever- and omnipresent paradigm of we the good guys and them the bad guys.

• Unfree media and de-democratisation – every theory of Western democracy includes a rather free, independent press as the sine qua non of democracy. In that light, sadly, democracy is now a thing of the past. The symbiotic relations between the state/government and the media should be obvious to citizens by now.

Over the decades, I’ve witnessed how, step-by-step, there is less will to criticise government policies. Further, it is true that we can all express ourselves in many more places than before – social media, comment fields, blogs, etc. – but power elites can ignore us in ways they did not dare to two-three decades ago. If criticised, people in power felt a need to explain and defend themselves – and even have honourable disagreements with their critics. And they wrote their answers themselves. Now it seems they don’t bother but leave that to their press spokespeople and public relations officers.

Paradoxically, all this is similar in tendency to ‘the authoritarian state’, which the West psycho-politically projects on those non-Western states they consider dangerous.

• The media ‘culture’ has changed away from public education – thus, between the 1970s, when I started doing media work, to around September 11, 2001, there existed a genuine, more frequent commitment to getting facts right; you were often asked to pedagogically explain to the audience what a conflict, for instance, was about, its background and how an event could be interpreted. The media saw public education as an important task. In addition, an agreement with them about themes to be taken up, concrete questions, and the time to be spent – was honoured to the extent possible. And there was no secondary agenda or people suddenly invited to counter you.

Political correctness has crept in everywhere. Today, therefore, you must be much more careful and ensure that you are not meant to merely play the role of an extra in a media show directed by people you don’t meet face-to-face.

There was consistent respect for one’s education and knowledge in the field of peace and some conflict areas that I knew quite well, both theoretically and from working on the ground. If, in the name of diversity, editors invited people with perspectives other than mine, it was not done to undermine my argument or frame me.

And there was simple fairness – not you alone against 5-10 other pro-NATO participants in favour of more armament, extended war or interventions. In today’s mainstream media, it is normal that all commentators and experts are pro-armament or in favour of their country’s participation in this or that war; there is not even an attempt to make it look like there is a balance.

However, if I – the peace expert – give an interview to a newspaper, the editor will see to it that my views are ‘explained’ and, to some extent, countered by experts rolling out the necessary arguments from the ruling politically correct narrative.

• Dialogue is out, debates dominate – debates are supposed to contain punchy arguments that end with ‘I am right, and you are wrong! – and, thus, with exclamation marks. Dialogues, on the other hand, are explorative, more like conversations with the parties listening carefully and asking questions to better understand the other side and get deeper down into the complexities of things. In dialogues, statements, therefore, end with question marks.

Thus polarisation and confrontation, politics as a football match is the order of the day. The public discusses who ‘won’ the debate, who was sassy, well-dressed, and knew how to avoid concrete answers, etc. not who had the qualitatively best argument.

The format is often built to prevent everyone from speaking at length and elaborate and present the underlying complexities of international politics. It tends to be all about positioning: Which side are you on – defended with twitter-like statements in need of no substantive knowledge. That also relieves the studio hosts from knowing the substance of the issues themselves; their role is merely to dribble arguments and sharpen differences among the debaters.

Today is about where you stand vis-a-vis this or that side in a conflict, your attitudes or opinions. If you operate outside the dominant manufactured narrative, you are not interesting, and your arguments don’t need elaboration. Instead, you get the critical questions and have to defend yourself – never those operating inside that narrative.

In short, public service was thrown out of the window long ago. Most of it is a blatant disservice except, of course, to those in power and, thus, elite service for those inside the MIMAC.

•

Admittedly, there is a risk that I have painted the past media world in a bit too rosy a light. Some of the above elements were present, or at least latent in the past – but they have become manifest and dominant now.

I want to emphasise, however, that I believe that 9/11 was a turning point – and by that, I do not mean the attack itself but the US reaction to it, including the commencement of the Global War On Terror, GWOT, and the fundamental(ist), dichotomised worldview – “you are either with us or with the enemy.”

This came a good decade after the end of the First Cold War around the 1990s, which the West triumphantly interpreted to mean that it had ‘won’ that war over the ‘other’ or other Western ‘brother’ – Communism in the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact – and its system was, therefore, the best thinkable.

This combination of seeing oneself first as a winner and then as a victim – whether true or not – makes for dangerous policy-making in an era where the same West is declining on all indicators but the military and is bound to fall sooner rather than later as the leader of the outgoing uni-polar world.

Macro-historical changes are happening before our eyes – if we care and dare to see them. Given this 30-year perspective, it is not that strange that the West’s mainstream media world has changed the way it has on various variables, as I have outlined above.

With the NATO-Russia conflict that plays out as a cynical proxy war in Ukraine (which does not imply that Ukraine is itself innocent), all these variables have been given one more turn.

So the end of the Cold War, September 11 and now the war in Ukraine are all turning points in the decay of our mainstream media. Few have initiated a debate about the role of the media around these three turning point, it is as if the decay of classical quality media work has been given full blast at every one of them.

Personally, I have never seen anything as poor as the media coverage of everything associated with Ukraine.

•

The constant characteristics – just more pronounced now

That said, I think there are at least three aspects that have remained the same over decades, but gotten more pronounced in the last 20-30 years:

• Every war is always two wars – namely, the one on the battlefield and the one in the media.

While the first is about the physical destruction of people, territory and property, the latter is about various kinds of mental-moral de(con)struction of truth and complexity, as well as every feeling of “our” co-responsibility; it is about creating demons and promoting fear and hate that will make it possible to squeeze more money out of us, the scared taxpayers, for more re-armament and making you forget everything about “unrealistic” options such as conflict analysis, mediation, negotiations, dialogue, peace plans, reconciliation, forgiveness, nonviolence and other – totally useless, of course! – methods with which to treat a conflict.

In terms of Ukraine today, the message is: “We” must win the war. But nobody seems to be concerned about what that means for Ukrainians.

In the field of international politics, we must understand that the Western mainstream media do not report wars; they participate in them and legitimize them – in all countries, now also the Western democracies. That includes the so-called public service media. And, above all, the so-called ‘free media’. They have invariably – freely – chosen to side with their own governments and their wars.

Those of us who often travel to places to see for ourselves have repeatedly made the same observation: The media image you travel out with about a conflict and war zone and its participants is extremely different from the real image and understanding you travel back with after having lived in those zones.

I first came across that phenomenon during the Yugoslavia dissolution wars. As part of my fact-finding, I did long interviews with many staff members of international organisations. Later, when we got to know each other, and I came back again and again – we went out and had lunch or dinner and more of a free conversation. I repeatedly heard sentences from UN, OSCE and other staff who had been there over many months or several years: “You know, Jan, when I come home to my country for a holiday or shorter visit and see what my national and local media write about the place where I serve, I have often wondered: Where have they been? There is no similarity between what I know about this place and what I read about it back home! And, not least, every complexity and fairness is gone. It’s so superficial, and it is scary to think of the fact that many decision-makers rely more on these very deficient media images than on the much more complex analyses we provide them with to help them make the best possible decisions.”

I have never been to a conflict or war zone where I did not experience that. Strongly. What you tell when you come home doesn’t fit the official, politically correct, simplified narrative. Your role automatically becomes that of the dissident – and that in a double sense: Not only do you offer other facts and perspectives than the generalised media image or narrative, but you also do so from a peace research and peace education perspective. Double dissident!

Over time, this media culture becomes de-moralising in the profession. And in times of crisis in the whole Western political sphere and the decline of the US Empire, these tendencies and mechanisms accelerate.

Now to the second one:

• Western media has always been navel-gazing – in Scandinavia, for instance, you’ll see extremely little news about the world outside your own country and the European Union, if it is not an earthquake or an accident in which your countrymen may have been involved, suffered or died.

G20 and G7 meetings, summits in BRICS and SCO – or the Belt And Road Initiative, BRI, which is the world’s and history’s largest cooperative project, high-level meetings in China’s political system – you name it – are hardly mentioned or covered by professional, knowledgeable journalists. It’s always been like that, structurally, but I believe that – in spite of globalisation – Western media are even more provincial. It is as if there is an implicit belief that ‘we do not have to learn from others because our role is to teach them.’

Traditionally, the media in The Rest have been much more open to what happened in The West and other parts of the world, which is – of course – a reflection of the global structure. But it means that you learn much more about the world as an entity if you read and watch media of The Rest.

In this era of relative decline of The West, this structure and self-centred attitude lead only one in one direction – to self-isolation and irrelevance in the eyes of The Rest.

And the third:

• War has always attracted the media more than peace – it’s well-known that bad news is good news. Most people get depressed, feel powerless and otherwise overwhelmed when having watched their prime-time news in the evening. I get the impression that more people today switch off – not the least the younger ones – or limit their news checking to a certain time – hours before they go to sleep.

Journalists always tell me that it is not their job to report on all the planes that land on time – but it is their job to report when a plane crashes. I accept that – but that is not the same as saying that news cannot also cover what would, generally, be deemed positive events and trends by millions of media consumers around the world.

Be this as it may, the media focus on the war where they ought to focus on the underlying conflicts – but how do you get footage of them? It is easier to show destruction, dead bodies and soldiers fighting. But what does it convey? That war is normal, part of human nature and probably impossible to eradicate. Take the World Press Photo competition; indeed truly moving photography of the highest technical quality. However, most of the pictures depict various types of violence and their consequences. One must ask: Is our world really that terrible, that ugly, that violent?

We have war reporters, heroes reporting from the midst of death and destruction, putting their own lives on the line. But when the war is over, they are covering a new war somewhere; they are not following up, and they don’t monitor peace and reconciliation or the emerging peaceful coexistence. We have virtually no mainstream coverage of, say, UN peacekeeping, how mediation and negotiations are carried out – or of peace processes in general. The media leave when the granates go silent.

War, death and destruction is the king theme of modern media. Drama, blood – and implicit participation in the second part of all wars, the media war about hearts and minds, takes priority.

I would argue that that priority is dead wrong – and that the way war reporting dominates is intellectually deficient as well as morally dubious. Or to put it crudely: It is low-quality media work. Here is why:

As you know, I am not a journalist, but I am a researcher who has made extensive use of media – and they of me. I’ve taught courses with journalists numerous times, including in war zones. I’ve worked for years in conflict and war zones.

Ever since my friends and colleagues Jake Lynch and Annabel McGoldrick published their eye-opening, pioneering and now classic “Peace Journalism – Conflict and Peace Building” (2005) and my mentor Johan Galtung and Jake Lynch, published their book – Reporting Conflict: New Directions in Peace Journalism (2010) – I’ve been convinced that the mainstream media’s way of informing the world about conflicts and wars is utterly deficient, ill-considered and incompatible with quality news reporting and documentary work. It is also war-promoting – whether so intended or not.

Antonio Rosa, the editor of Transcend Media Service, TMS, says that “Galtung’s simple point is that peace journalism is to ask two questions (in addition to the cliché ones such as, ‘how many bombs were dropped, how many buildings destroyed, how many casualties/wounded, who is winning’, etc.): “What is the conflict about? What could be the solutions?”

And he continues – “the time has come for “peace journalists” to write not only about war, but also about its causes, prevention, and ways to restore peace by nonviolent means and promoting peace as a value. They need not invent themselves solutions to conflicts–in the same way that health journalists need not invent cures for diseases themselves; they ask specialists.”

Jake Lynch formulates it this way: “Peace journalism is when editors and reporters make choices–about what to report, and how to report it–that create opportunities for society at large to consider and to value non-violent responses to conflict.” And peace journalism:

- “Explores the backgrounds and contexts of conflict formation, presenting causes and options on every side (not just ‘both sides’);

- Gives voice to the views of all rival parties, from all levels;

- Offers creative ideas for conflict resolution, development, peacemaking and peacekeeping;

- Exposes lies, cover-up attempts and culprits on all sides, and reveals excesses committed by, and suffering inflicted on, peoples of all parties;

- Pays attention to peace stories and post-war developments.“

This is not the place to write at length about peace journalism; read the two books and, for instance, this article by Steven Youngblood. The readers will already have grasped the tremendous difference from everything they see in today’s mainstream media – as well as the tremendous potential of this entirely different approach to reporting conflicts and war.

We should have much more peace journalism and, while also keeping war reporting because wars are part of reality, we should reduce it to a fraction of the media coverage. The media world contributes overwhelmingly to militarist thinking, armament and war, but they can choose to do it differently by balancing that sort of journalism with the alternative peace journalism approach.

But will they? In my view, not as long as they are part of MIMAC.

🔶

The media don’t have to be an obstacle and a manipulator forever.

Above I have put together the overall media system and its structural trends as I have subjectively experienced them over decades. If I ask myself what has fuelled this across-the-board decay, the answer is simple: They’ve grown concomitantly with the decline of The West vis-a-vis The Rest.

The distortions, narratives, propaganda and planted stories and outright lies and omissions have accelerated and become more desperate during the last few decades – more and more for each (failed) intervention and war – and now focusing more and more money and energy short-term on Russia and long-term on China.

The systematic psycho-political projection of the West’s own dark disinformation shadows unto ‘the others’ will become increasingly difficult to sell. Sooner rather than later, people will wake up to what I call their ‘Pravda Moment’ – the moment they see clearly the extent to which they have been taken for a political correctness ride. That is likely to happen along with the system breakdown and the problems decision makers will face at explaining why they failed miserably in achieving the goals they set – such as re-arming tremendously and destroy Russia and also pay the bills for it and devote themselves to stop climate change and keep China down and remain the leader of the world and provide welfare, growth and good lives for their citizens.

The West has set itself on mission impossible. Decision-makers and the mainstream media are together in it all.

•

Finally, I would very much like to add that I have also had lots of very pleasant and mutually beneficial encounters with media individuals – people who prepared themselves well, treated me with respect, didn’t frame me, etc. It has happened in Western media and it happens almost daily with all those I now work with.

Also, I encounter, work with and post fine articles almost every day by brilliant journalists, people who have civil courage and the knowledge needed to make a huge difference. There is a tremendously rich undergrowth worldwide. They all teach me things and give me hope. What I have done above is to focus on the mainstream media world, and that gives me no hope anymore.

I believe the (un)balance between the type rough types of journalism will soon change.

Likewise, I have enjoyed teaching peace and conflict resolution to hundreds of journalists and students of journalism, both in war zones, at single guest lectures and also at what was called the Fortbildning för Journalister (Continued Journalism Training), FOJO, in Kalmar, Sweden – today FOJO Linnaeus University.

Peace-including journalism does not imply that reporters, journalists and editors shall promote peace or otherwise see themselves as advocates of this and that particular goal, values or conflict solutions. It means, rather, quality media work in and about conflicts and war.

The world must find ways to take the ‘M’ out of the MIMAC. Journalism as a profession and the mainstream media – specifically – must not continue to serve as a promoter of war and – generally – continue to be the biggest single obstacles to understanding our time, the world and humanity in it.

That remains an integral part of the broader, ongoing struggle to reduce all kinds of violence and create a more peaceful world.

Stop for a while and think – think differently. And we can do it.